IN economics, as in medicine, treating the symptom while ignoring the disease is not a cure; it is malpractice.

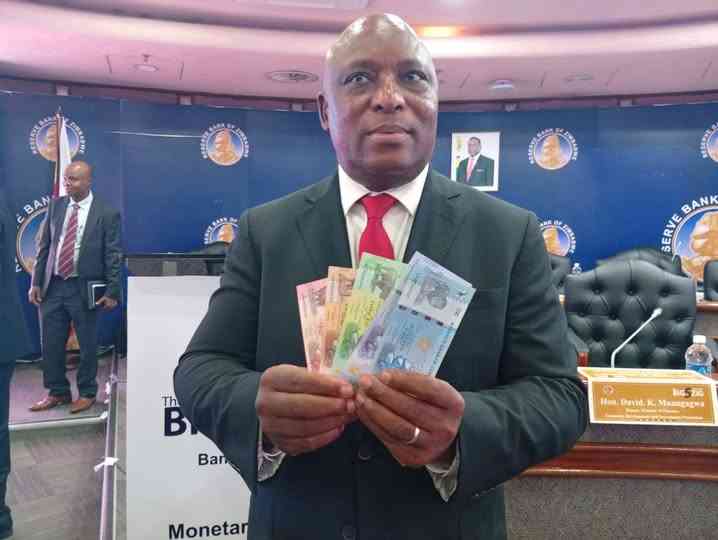

For decades, Zimbabweans have watched a dizzying parade of currencies — the Zimbabwe dollar (ZWL), the bearer cheque, the bond note and now the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) — enter the stage with fanfare only to exit in disgrace.

Each failure is met with the same official bewilderment and the same hunt for saboteurs.

However, as I argue in my forthcoming book, Black Poverty: A Story of Leadership and Policy Failures, our cyclic currency collapse is not a monetary problem.

It is the inevitable, final symptom of systemic institutional decay. The collapse of the ZiG, which has already seen significant depreciation since its April 2024 launch, is not a failure of gold backing; it is a failure of trust backing.

Until we address the structural preference for the “political means” over the “economic means” of wealth creation, no currency — no matter what precious metal it is tethered to — can survive.

The ovarian lottery and the hidden tax

The tragedy of the modern Zimbabwean experience is best understood through the concept of the “ovarian lottery”.

- ‘Inflation could shoot to 700% by April next year’

- Trafigura seeks control of Zim metals over debts

- Smuggling of gems bleeding Zim’s economy

- Erik ten Hag: Manchester United appoint Ajax boss as club’s new manager

Keep Reading

A child born in Singapore or South Korea today inherits a system designed to act as a hidden subsidy to their effort; their savings are safe, and their property is secure. A child born in Zimbabwe inherits a system that acts as a hidden tax on their existence. This tax is not just the VAT you pay at the till; it is the inflation that liquidates your pension and the policy inconsistency that renders your business plan obsolete before the ink is dry.

When a government funds its deficits by printing money — essentially taxing the citizenry through inflation — it is engaging in what sociologist Franz Oppenheimer called the “political means” of acquiring wealth.

Instead of creating value through production (the “Economic Means”), the state uses its power to transfer wealth from the saver to the sovereign. The result is not just poverty; it is the systematic destruction of the future.

The architecture of failure

We must cut through the comfortable rhetoric of external blame. Our economic stagnation is not the result of unalterable destiny or solely external sanctions; it is the result of specific “pilot errors” in our institutional design.

The data is unequivocal. Between 1980 and 2005, while Asian economies were skyrocketing, Zimbabwe’s Total Factor Productivity — a measure of economic efficiency and innovation — collapsed from 80% of US levels to just 20%.

Why? Because we built an economy based on patronage rather than production. We expanded a massive, unproductive civil service that consumed 41% of the recurrent budget by 1989, crowding out the capital investment needed for roads, dams and factories. We compounded this by prioritising political survival over economic rationality. The decision to enter the Democratic Republic of Congo war in 1998, for example, was not just a military adventure; it was a massive opportunity cost.

A verifiable counterfactual suggests that US$100 million invested in a standard index fund rather than that war would have grown to over US$1 billion by 2024. That is a billion dollars of missing infrastructure, lost to political vanity.

The property rights deficit

The most critical pilot error, however, was the destruction of property rights. The fast track land reform programme is often debated in terms of racial justice or historical grievance. But from an economic standpoint, its method was catastrophic because it destroyed collateral. When the state nullified title deeds, it did not just seize land; it severed the link between the banking sector and the productive sector. You cannot build a modern financial system in an environment where assets can be arbitrarily seized by the state. This is why the ZiG struggles. A currency is a certificate of trust in the state’s institutions. If the state does not respect the property rights of a farmer or a business owner, why would the market trust it to respect the value of a banknote?

Learning from Deng, not dogma

The solution lies not in finding a new governor for the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), John Mushyavanhu, but in a fundamental ideological pivot.

We must look to the example of Deng Xiaoping’s China.