Zimbabwean industries are piling pressure on fiscal authorities to overhaul a Value-Added Tax (VAT) system that has become a persistent drain on corporate liquidity, proposing a special revolving refund fund and a new class of tradable government-backed bonds to unlock millions of dollars trapped in unpaid refunds.

At the centre of the proposal by the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC) is a fundamental reform of government’s long-criticised “pay now, reimburse later” VAT model, which forces firms to remit tax long before they have received payment from customers — including the State itself.

Under the proposed framework, a fixed percentage of monthly VAT collections would be automatically ring-fenced and channelled into a dedicated refund pool, while verified VAT refund claims would be converted into government-guaranteed instruments that companies could trade on the stock market or use to settle other tax obligations.

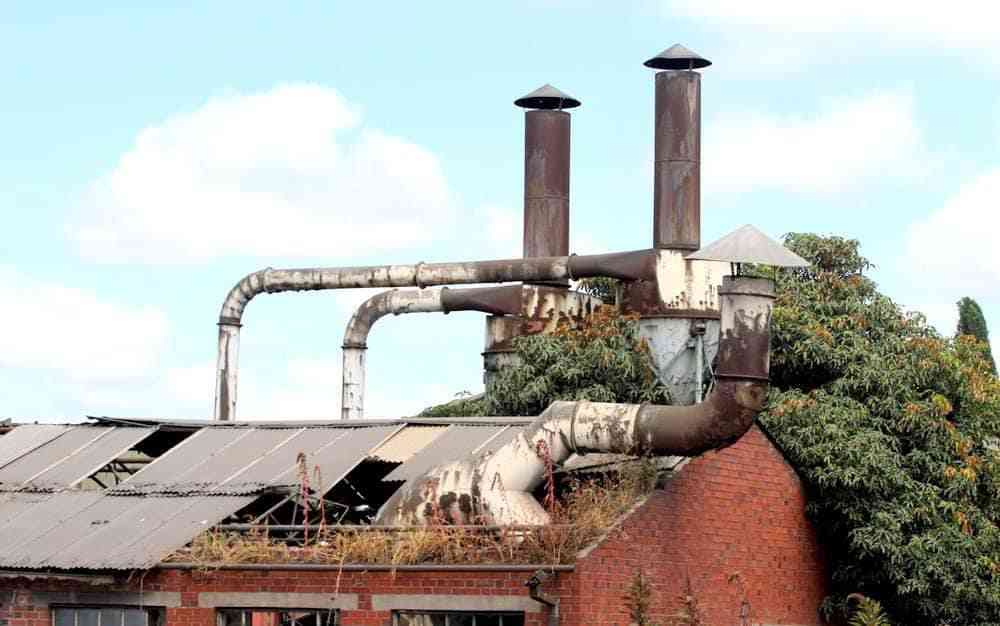

The initiative comes against the backdrop of rising tax pressures following the 2026 national budget, with industry warning mounting statutory obligations are worsening already fragile cash flows and undermining productive capacity across the economy.

In its detailed submission, the ZNCC argues chronic VAT refund delays have become one of the most corrosive features of Zimbabwe’s tax system, compounding liquidity stress at a time when access to affordable credit remains limited and interest rates punitive.

The chamber’s 2025 Annual State of Industry and Commerce survey underscores the urgency of reform. It revealed that administrative burdens stemming from more than 50 separate tax payments consume about 242 hours per firm annually in sheer compliance time — a heavy cost for an economy struggling to rebuild competitiveness.

VAT rules are singled out as particularly onerous. Businesses are required to remit output VAT within 30 days of issuing an invoice, regardless of whether payment has been received. This, industry argues, creates a structural mismatch between tax obligations and actual cash inflows.

“Current tax regulations sometimes demand tax payments in situations misaligned with business cash flows, exacerbating liquidity issues,” the chamber stated.

- Zim needs committed leaders to escape political, economic quicksands

- Redcliff uses land to pay off water debt

- In Full: Nineteenth post-cabinet press briefing: July 05, 2022

- Australia floods worsen as thousands more flee Sydney homes

Keep Reading

“A clear example is VAT: Zimbabwe’s VAT Act requires that Output VAT be remitted by the 15th of the month following an invoice, even if the customer has not paid yet.”

“This is especially problematic when the customer is the government itself. It’s public knowledge that government departments can take 6+ months to pay suppliers, yet the supplier must pay VAT within 30 days of invoicing. This ‘pay now, reimburse later’ setup means businesses finance the Treasury in the interim, squeezing working capital.”

It is this distortion that the proposed Revolving VAT Refund Fund seeks to correct.

The ZNCC wants the fund to be established as a dedicated, ring-fenced account, legally separate from general government revenues and used exclusively for the settlement of verified VAT refunds. To ensure sustainability, the chamber proposes that 5% of all monthly VAT collections be automatically allocated to the fund.

Governance would be shared between the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority, the Ministry of Finance and private-sector representatives, operating under strict audit controls to guard against diversion and restore confidence in the refund process.

Beyond cash-based refunds, the chamber is also pushing for the introduction of a VAT Refund Bond — a government-guaranteed instrument issued directly to companies with validated refund claims.

Instead of waiting indefinitely for cash settlements, affected firms would receive bonds with maturities ranging from six to 24 months. These instruments could either be held to maturity and redeemed at par, or sold immediately on the secondary market, including on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE), allowing companies to unlock liquidity when it is most needed.

“Holders may use VAT Refund Notes to pay any domestic tax or sell them on the ZSE; banks can discount them for working capital,” the ZNCC explained.

The proposal effectively seeks to transform VAT refund arrears — shifting risk away from businesses and introducing market discipline into the refund process.

However, significant legal and policy hurdles remain.

For the system to function, amendments would be required to both the Public Debt Management Act and the VAT Act to formally recognise VAT refund bonds as lawful settlement instruments and to provide explicit government guarantees.

The ZNCC has recommended piloting the bond programme with large, audited exporters — traditionally the biggest VAT refund claimants — before extending it across the wider economy.

The proposals come amid sustained complaints from major listed companies, including Innscor Africa, Zimplats, National Foods and Delta Corporation, which have repeatedly warned that Zimbabwe’s tax regime prioritises Treasury cash flow over business viability.

“The tax burden in Zimbabwe is not just about rates, but about the sheer number of tax payments and the effort required to comply,” the ZNCC said, citing a World Bank report which shows Zimbabwe’s 51 distinct annual tax payments are among the highest globally.

“By comparison, advanced economies have as few as three to 11,” the ZNCC said.

“These indicators reflect systemic inefficiencies: archaic manual processes, lack of consolidated filing, and frequent filing intervals. Many businesses, especially SMEs, struggle to meet all these obligations, which can lead to late payments, penalties, or opting out of the formal system altogether,” the chamber noted.

Industry argues the cumulative effect of monthly VAT and Pay As You Earn returns, quarterly income tax payments, National Social Security Authority contributions, transaction taxes and multiple licensing fees is a tax architecture that drains management time, weakens corporate balance sheets and discourages formalisation.

Without structural reform, business leaders warn, VAT will remain less a consumption tax and more an involuntary loan to the State — one that companies can ill afford to extend.

Across Africa, several countries have moved decisively to address VAT refund bottlenecks through institutional reform and market-based solutions.

South Africa operates a risk-based VAT refund system through the South African Revenue Service, where compliant taxpayers receive refunds within 21 days, supported by automated audits and strong enforcement capacity.

Rwanda has digitised VAT administration end-to-end, allowing refunds to be processed within 15 days for low-risk taxpayers, with penalties imposed on the tax authority for unjustified delays — a powerful accountability mechanism.

Kenya introduced VAT refund offsetting, allowing businesses to net refunds against other tax liabilities, while also issuing infrastructure bonds and tax-offset instruments to manage government obligations transparently.

Morocco established a dedicated VAT refund account funded directly from VAT receipts, insulating refunds from broader fiscal pressures and restoring business confidence.

These examples show that predictable refunds, ring-fenced funding and tradable instruments are not fiscal luxuries, but essential tools for sustaining private-sector growth. For Zimbabwe, adopting similar mechanisms could mark a decisive shift from ad hoc tax administration towards a modern, investment-friendly fiscal regime.