THE Zimbabwe Investment and Development Agency (Zida) reported that as of the end of last year, Zimbabwe’s real estate market was projected to have reached US$119 billion valuation. However, with the looming de-dollarisation transition to a mono-currency by 2030, property developers are nervous that most of their investments will lose significant value. This, coupled with heavy regulations, high taxes and levies, and a cumbersome permit process, has got property developers re-evaluating their positions. Our business reporter Concilia Mupezeni (CM) spoke with the Property Developers Association of Zimbabwe’s interim chairman Arnold Khanda (AK) to discuss these dynamics. Below are excerpts from the interview:

CM: How will pricing, contracts, and financing change for both residential and commercial developments as the economy shifts toward ZiG?

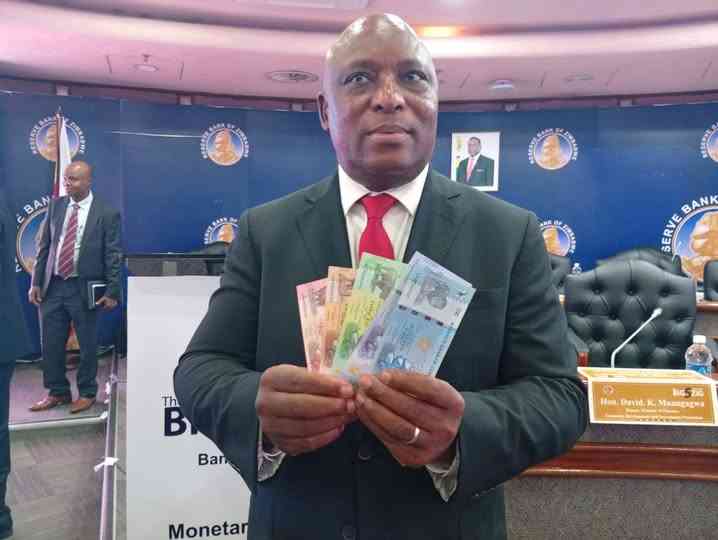

AK: I perceive ZiG as a risky currency. Whilst there is growing confidence in the government’s fiscal discipline, that confidence has not yet truly transformed into confidence in ZiG. The current governor of the Reserve Bank John Mushayavanhu was previously with FBC, and under his leadership, FBC became a powerhouse in the property development field, so we have a lot of confidence in him as developers, as he is one of us. However, we wait to hear from him for a clear direction and way forward come 2030. So, until the governor and Finance minister Mthuli Ncube give our sector a clear road map, I doubt any developer will be pricing property in ZiG, especially if it is not a cash sale and terms are being offered.

CM: There is significant growth in property developments. Is there enough titled land to sustain both commercial and residential projects without risking oversupply or legal bottlenecks?

AK: There is more than enough land. Zimbabwe is just under 387 000 square kilometres and its largest city by a long way is Harare, which occupies around 20% of Zimbabwe. That said, whilst land is running out in Harare, it is still available in other cities. But to manage this sacred resource, the government has instituted a densification programme. Harare alone has the potential to double the number of households in two years if all the relevant planning permits were to be made easily available.

CM: Does the current land tenure and approval system affect development timelines, investor confidence, and project risks?

AK: The current approval system for development permits is the single biggest stumbling block for us as developers. Its uncertainty and cumbersome nature make it a nightmare. This is made worse by the sheer time it takes. This makes planning the financing almost impossible. For those without their own funds, this is the ridiculous situation developers find themselves in due to the chaotic permit approval process. Often a permit arrives when the developer has moved on to other projects, so this makes arranging finance a nightmare and causes many projects to be stillborn. Investors cannot be put on hold indefinitely for a process that has no fixed time limit. Permits can take anything between four months to two years; it is a total pig’s breakfast.

CM: What impact does the 1% wealth tax on properties valued above US$250 000 have on investor appetite, particularly for high-end residential and commercial projects?

- Calls for sanctions removal intensifies

- PPPs essential to addressing infrastructural deficits

- Lithium exports to surpass gold, says Zida chief

- Zim’s cannabis hopefuls face EU blowback

Keep Reading

AK: We all hope this will not come to pass. Properties in Zimbabwe have become a source of wealth preservation and pension provision, offering financial security and passive income especially as people retire. The average worker may have to work the majority of their working life to buy a property valued at over US$250 000. That said, with inflation and the lack of housing stock, a US$50 000 property bought today could be worth over US$250 000 at one’s retirement. So, this 1% tax will effectively be a tax on people’s pensions. Until such a time that pensions start paying a living annuity, this policy will greatly affect our pensioners and the property development market, as houses will lose their shine as retirement assets.

Retirement and pensions aside, a house valued at US$250 000, held as an investment property, will attract a rental of between US$500 and US$800 depending on a lot of factors. If we take a mid-range of US$650, giving us an income of US$7 800 per annum, and assume we have 75% occupancy, that is an income of US$5 850 in the year. That means the 1% levy on US$250 000 will be taking away over 40% (approximately 42,7%) of the rental income. This is on top of the tax that would need to be paid on the rental income.

At least with rental income, the expenses incurred are deducted from the taxable income, but with this brutish tax you could end up being forced to pay US$2 500 on a property worth US$250 000 that you bought for US$50 000 ten years ago and has cost you US$3 000 to renovate and maintain in the year. So, this proposed tax is a potential industry killer.

CM: How do general taxes, levies, and municipal charges influence development decisions, and what regulatory reforms would make Zimbabwe more attractive for investors?

AK: The amount of taxes and levies surrounding development projects is simply ridiculous. As developers, we feel like a well-done “pig on a spit”; everyone wants to take a slice of you. A typical application for cluster homes has around US$5 000 in application fees. This comes from a previous fee of just US$250 for any number of clusters.

This is after paying architects, surveyors, town planners, and engineers for a project that may or may not be approved. After a few other costs, when the permit finally comes out – which may approve something totally different from what was applied for initially, requiring more work from architects and engineers, etc. – one is supposed to pay the city to have water, sewer, and driveway designs approved. This infrastructure will be handed over to the city once installed.

For our example, that would be around US$15 000. After getting this approval, there is an endowment fee of around 10% payable to the city.

The city now insists on an Environmental Impact Assessment, for which you have to get comments from stakeholders such as Zesa Holdings and the Zimbabwe National Water Authority, and they all charge around US$1 500 for this. The Environmental Management Agency insists on 2% of the total project cost as fees.

Thereafter, for a medium-sized unit, plan application fees are around US$20 000. To put in the sewer and the water, the council makes you pay to dig alongside the road, and do not dare try crossing the road – the fees would kill an elephant! So, all in all, levies and permits can take up 25% or more of total project costs, which are ridiculously high and create a big barrier to entry for small developers.

CM: Retail properties dominate new developments. Do you see sufficient long-term demand for commercial spaces, or is there a risk of oversaturation?

AK: As we move towards cluster living, more and more retail will be required. Long commutes to buy everyday items, and even appliances, will become a thing of the past.

The future will be that you can work, play, eat out, and buy hardware, even cars, within a 15-minute drive from your home. You should have a hospital or medical facility, a bank, and a school all within that radius.

This will result in the need for more and more retail space. With the rise in small entrepreneurs, the sizes of shops may reduce but the number will increase. Shops will increasingly become specialised, but this will increase the number required.

CM: Given the rise in population and projected growth, how strong is demand for residential and affordable housing developments?

AK: The demand is overwhelming. Harare alone has a shortage of over one million housing units, and other cities are not far behind. We have a very vibrant diaspora, and they all want to come back home someday, so they will also join the market and, in fact, are already a big player in it.

The government needs to avail land for low-cost housing to developers to encourage its provision, and lower taxes and levies and simplify the application process. Government and local authorities need to look at developers as partners, not adversaries. Commercial properties are driven by residential properties, so the balance is always there.

CM: Are the current liquidity constraints, such as limited access to finance and rising borrowing costs, affecting property developers’ ability to start or complete projects?

AK: Developers have become money engineers and financial gymnasts, starting with the most popular model – the joint venture – where landowners partner with developers, thus freeing the developer’s capital for investing in the development and not the land.

Also common is the off-plan sale, where the property or stand is sold whilst being built or serviced.

This is where most fall down, as cash flow management is critical and because there is no financing.

Sales are erratic, instalments are unpredictable in both consistency and amount, and the level of financial gymnastics required is Olympic standard! This makes the business very stressful and highly volatile. One wrong move and the project can implode.