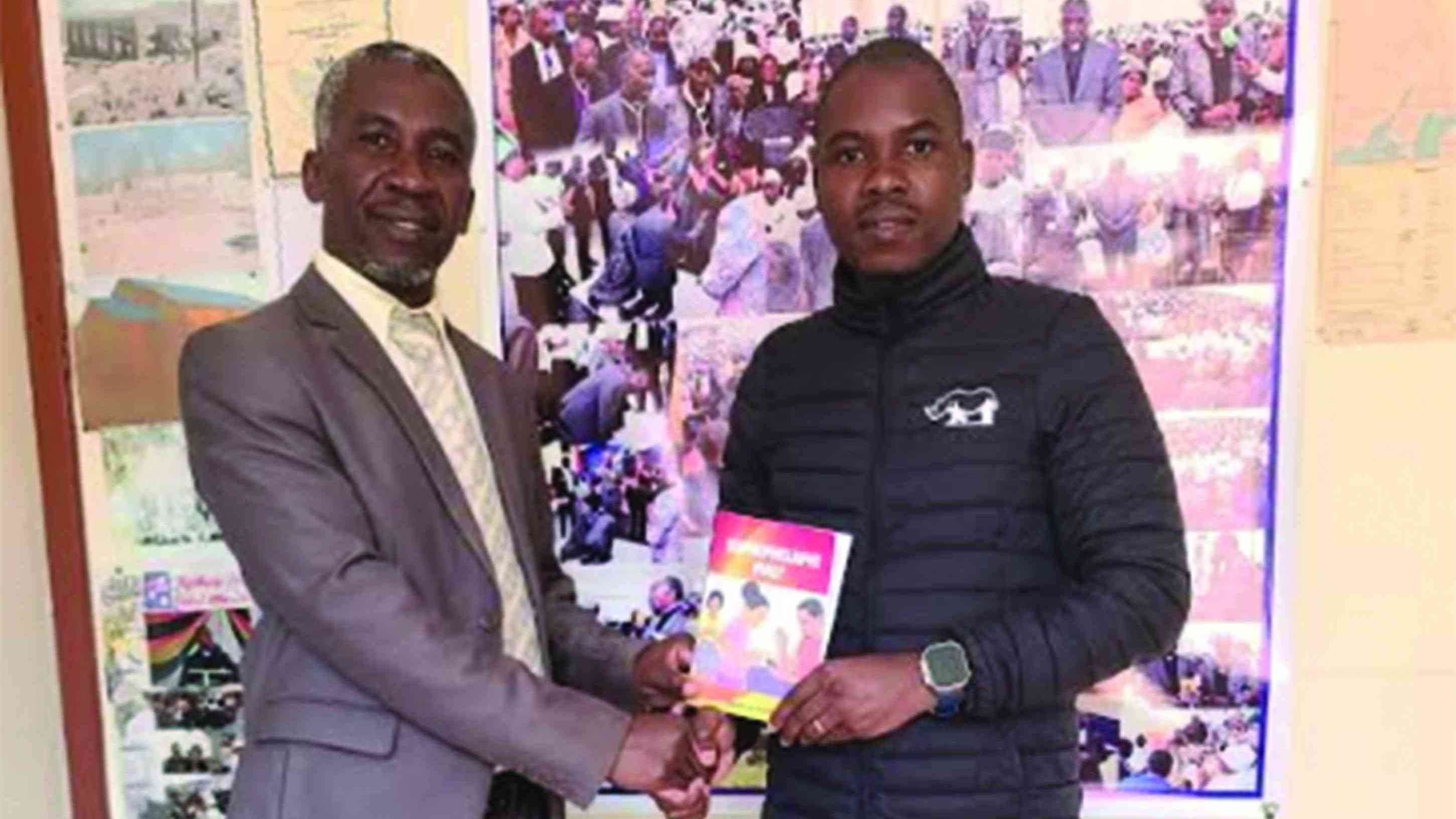

MTHANDAZO Nyoni’s novel titled Sophephelaphi Pho? (Where can we find refuge?), published in 2025 by Radiant Publishing Company, is a significant and timely intervention in contemporary isiNdebele literature.

More than a mere novel, it is a cultural manifesto, a social alarm, and a poignant exploration of the crises facing modern Zimbabwean society, particularly its youth.

Written with the unflinching eye of a journalist, Nyoni’s work challenges the dominance of English in literary circles while confronting some of the most distressing realities of 21st-century life.

The novel’s power derives from its layered engagement with interconnected themes of alienation, betrayal, and the search for safety.

Its primary focus is the dissolution of the traditional family unit, not through physical displacement but through digital distraction.

Nyoni meticulously portrays homes where smartphones, tablets, and televisions have usurped the role of communal conversation.

Parents are depicted as physically present but emotionally absent, “busy chasing their careers, jobs, status”, in a relentless cycle that leaves children isolated and unheard.

This critique moves beyond simple generational complaint to identify a profound spiritual and social poverty, where the pursuit of external validation erodes the fundamental bonds of care.

This domestic failure forces the question of refuge onto public institutions, primarily the school, which the novel reveals as a site of even greater peril.

The harrowing narrative of Nomathemba Dube, a Grade Seven learner raped by her class teacher, forms the ethical core of the book. Her story is a master class in portraying compounded trauma: the initial violation, the ensuing pregnancy, and the subsequent, deafening silence from the adults in her life.

Her parents, absorbed in their digital worlds, offer no ear; the school authorities, implied to be complicit or wilfully blind, offer no justice.

Nyoni extends his indictment to the wider judicial system with the searing question: “Where can we find refuge if rapists are arrested but later released under unclear circumstances?”

This progression — from negligent home to predatory school to corrupt judiciary — creates a terrifyingly closed circuit from which the child sees no escape.

The titular cry, “Where can we find refuge?” thus becomes a desperate lament for an entire generation betrayed by every pillar of society.

Nyoni employs a direct, accessible narrative style, informed by his journalistic background. The prose is clear and purposeful, prioritising emotional impact and social message over lyrical flourish.

This approach is highly effective, ensuring the novel’s urgent themes are communicated without obscurity. The plot is structured to maximise didactic and emotional force, using Nomathemba’s story as a central, powerful case study around which other examples of familial breakdown orbit.

Characterisation serves the novel’s thematic ambitions. Figures such as Nomathemba’s parents are archetypes of modern neglect, not monstrous, but tragically distracted, making their failure all the more recognisable and condemnable.

Nomathemba herself is portrayed with empathy and clarity; her voice embodies the confusion and despair of the abandoned child.

The predatory teacher represents the abuse of authority, but the novel’s greater horror lies in the system that enables him. The characters collectively illustrate a societal sickness rather than individual psychopathologies, which is central to Nyoni’s broader critique.

The decision to write this novel in isiNdebele is arguably its most profound political and cultural statement. In a publishing landscape where indigenous languages are often marginalised, Nyoni asserts the vitality and relevance of isiNdebele for discussing complex, contemporary issues.

He demonstrates that the language is not merely a vessel for folklore or historical narrative but a robust tool for modern social critique.

This act of writing contributes directly to language preservation, fosters cultural pride, and encourages readership among isiNdebele-speaking youth, offering them a literary mirror in their mother tongue. It positions the novel within a vital tradition of linguistic activism in African literature.

The novel could serve as a set book for Grade Seven as it raises critical, real-world issues — sexual abuse, neglect, institutional failure — that are tragically relevant to many learners. As a teaching tool, it could powerfully promote isiNdebele literacy, stimulate essential conversations about safety and consent, and foster empathy.

It directly answers the novel’s own plea for schools to “create safe space for pupils” by providing a textual basis for such dialogue.

While the novel’s strengths are undeniable, its unwavering focus on social message can occasionally render the narrative somewhat didactic, with character development sometimes secondary to thematic illustration.

The resolution of the story — whether it offers any glimpse of hope or remains in despair — would significantly shape its ultimate impact and reception.

Despite these considerations, Sophephelaphi Pho? is a courageous and essential work. Nyoni has crafted a novel that functions as both a diagnosis of societal illness and a clarion call for communal responsibility.

It is a testament to the power of indigenous-language literature to engage with the most pressing issues of the day.

Uncomfortable, urgent, and deeply moving, Sophephelaphi Pho? does not allow its reader the luxury of indifference. It demands that we listen to the child’s cry and, collectively, build the refuge that is so desperately sought.

I recommend this book for children in grade Six and Seven, as well as for youth and parents. — Staff Writer.