Corruption remains one of the most persistent and complex global governance challenges, with far-reaching consequences for socio-economic development, public sector accountability, macroeconomic stability, and the protection of human rights (Valérian, 2024).

Extensive empirical research demonstrates that high levels of corruption are associated with reduced public service delivery, increased inequality, constrained economic growth, and declining public trust in institutions.

In developing country contexts, corruption exacerbates poverty, distorts resource allocation making it both a development and governance concern of global significance.

As governments, multilateral institutions, and civil society actors increasingly pursue evidence-based anti-corruption strategies, the ability to systematically measure and compare corruption across countries has become essential.

Robust measurement frameworks are critical not only for diagnosing corruption risks but also for informing policy design, tracking reform progress, enabling cross-country comparison, and strengthening accountability.

However, corruption is inherently difficult to measure directly. Corrupt acts are clandestine, illegal, and rarely captured in official records, while victims and perpetrators alike often have incentives to conceal wrongdoing. These challenges have necessitated the use of indirect measurement approaches that rely on perceptions, expert assessments, and risk evaluations.

- Background to the Corruption Perceptions Index

Prior to the mid-1990s, no globally comparable tool existed to systematically assess public-sector corruption across countries. In response to this methodological gap, Transparency International introduced the CPI in 1995 (Transparency International, 1995).

The CPI has since become the most widely recognised and frequently cited global governance indicator of public-sector corruption, shaping international policy debates, funding partner engagements, investment decisions, and national reform agendas.

- Teachers, other civil servants face off

- Veld fire management strategies for 2022

- Lobby group bemoans impact of graft on women

- Magistrate in court for abuse of power

Keep Reading

Published annually, the CPI measures perceived levels of corruption in the public sector based on expert assessments and surveys of business professionals. The index aggregates data from up to thirteen (and a minimum of three) independent sources, including international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank, policy think tanks, and private risk and consulting organizations such as the World Economic Forum (WEF) to name a few.

These sources assess a range of corruption-related risks, including bribery, misuse of public funds, abuse of public office, state capture, and the effectiveness of anti-corruption frameworks.

The CPI applies a rigorous standardisation process to transform all inputs into a common scale ranging from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean), enabling meaningful cross-country comparison (Transparency International, 2025).

Over the past decade, Zimbabwe’s performance on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) has consistently remained below the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) regional average whilst recording only marginal and uneven improvements in recent years.

This persistent underperformance has occurred against a backdrop of sustained political and policy commitments to combat corruption, such as the establishment and strengthening of anti-corruption institutions, the promulgation of a National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) and reforms to public procurement systems to name a few.

While these initiatives signal formal adherence to international and regional anti-corruption norms, their impact is yet to translate into significant or sustained improvements in Zimbabwe’s perceived levels of public-sector integrity.

It is within this context that Transparency International Zimbabwe (TI Z)[1], through this paper, seeks to identify strategic policy entry points for policymakers to strengthen the national anti-corruption drive and improving governance outcomes, including performance on the CPI.

The paper provides a detailed examination of the CPI data sources (called sub-indicators), explaining both their focus areas and methodology. Concurrently the trends in the performance of Zimbabwe are also critically examined against each sub-indicator. In doing so, it demonstrates how these sub-indicators are blended according to Transparency International’s formula to form a composite CPI, presenting opportunities for targeted interventions that could influence future national scores and other governance indices.

- An overview of the Corruption Perceptions Index

The CPI plays a critical role in advancing global anti-corruption efforts by providing a clear, standardized, and internationally comparable measure of public sector corruption.

Its strength lies in its ability to synthesize diverse, credible data sources into a single, easily interpretable score, enabling policymakers, development partners, and civil society to identify trends, benchmark performance, and assess progress over time. By focusing on expert and business assessments, the CPI captures informed perspectives that are closely linked to investment risk, governance quality, and institutional effectiveness (Transparency International, 2024). It captures multiple manifestations of corruption in the public sector, including bribery, diversion of public funds, and the abuse of public office for private gain.

However, the CPI does not capture several important dimensions of corruption, such as citizens’ direct experiences or perceptions, tax fraud, illicit financial flows, money-laundering, the role of professional enablers (including lawyers and accountants), private sector corruption, or corrupt practices within informal economies and markets (Transparency International, 2024).

The CPI’s methodological rigor enhances its credibility. The CPI is reliable than each source taken separately because it compensates for eventual errors among sources by taking the average of at least three independent sources and potentially as many as 13.

The use of multiple sources reduces reliance on any single dataset, while strict inclusion criteria ensure that results are statistically reliable.

The standardisation process allows for meaningful comparison across countries and over time, particularly from the 2012 baseline onward. This consistency makes the CPI a valuable tool for tracking reforms, evaluating governance outcomes, and informing policy dialogue at both national and international levels.

This standardised approach enables meaningful comparisons, facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of political and economic transformations.

Beyond measurement, the CPI has significant normative and practical value. It raises public awareness about corruption, encourages transparency, and creates incentives for governments to strengthen transparency, accountability and integrity mechanisms.

Countries that demonstrate improvement in CPI scores often attract greater investor confidence and donor support, reinforcing the link between good governance and sustainable development.

- Trends and analysis of Zimbabwe in the CPI

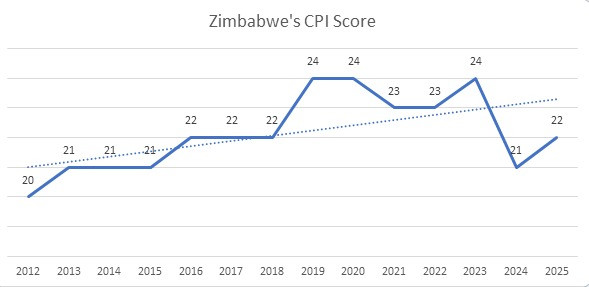

Below is a clear, policy-oriented analysis explaining the rise (2012–2020) and subsequent decline (2021-2025) in Zimbabwe’s CPI. Zimbabwe’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) shows a gradual improvement from 2012 to 2020, followed by a reversal and decline from 2021 to 2025. These trends reflect shifts in governance reforms, political transitions, institutional capacity, and broader economic conditions.

Figure 1: Zimbabwe's Corruption Perceptions Index: Key Trends and Insights

**Source: Author’s own compilation

Between 2012 and 2025, Zimbabwe recorded a modest but notable improvement in its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) score, rising from 20 to a peak of 24. This gradual upward movement reflected incremental progress in strengthening public-sector integrity frameworks, albeit within a context of uneven and often incomplete reform implementation.

The adoption of the 2013 Constitution marked an important milestone by entrenching principles of accountability, transparency, and institutional oversight, which positively influenced expert assessments of governance quality.

The political transition of 2017 further generated optimism around prospects for improved governance and accountability. This period was characterised by renewed commitments to anti-corruption reforms, the launch of high-profile investigations, and deliberate efforts to re-engage international partners and financial institutions.

These initiatives increased external scrutiny of public financial management and governance practices, while early public-sector reforms and digitalisation efforts, though limited in scope, signaled intent to reduce discretionary decision-making and improve service delivery. Collectively, these developments contributed to a temporary improvement in Zimbabwe’s CPI score and international standing.

However, from 2021 to 2024, Zimbabwe’s CPI score declined from 24 to 21, reflecting growing concerns among experts and business professionals regarding governance quality and corruption risks.

The 2024 score represents a significant deterioration, returning Zimbabwe to one of its lowest global rankings at 158 out of 180 countries, following a brief and unsustained improvement in 2023.

This downward trend highlights the fragility of earlier gains and underscores persistent skepticism about the credibility and effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts. Zimbabwe recorded a small but meaningful uptick in the 2025 CPI, with its score edging up from 21 to 22 - a sign of cautious movement in the right direction.

Importantly, the decline in CPI performance must be understood within the broader context of reform dynamics and perception formation. The anti-corruption reforms introduced from 2017 onwards, and later under the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS I), generated extensive national and international debate, heightened media scrutiny, and increased public awareness of corruption. In the short term, this intensified exposure of corruption risks and governance failures likely contributed to a deterioration in perceived integrity.

Over the longer term, however, sustained reform implementation and demonstrable accountability are expected to translate into improved perceptions and measurable governance gains.

The recent decline is also attributable to a persistent gap between formal policy commitments and practical enforcement. While Zimbabwe has adopted a range of anti-corruption laws, strategies, and institutional frameworks, enforcement remains weak and inconsistent, leading to perceptions that reforms are largely symbolic rather than transformative.

High-profile corruption allegations, particularly in public procurement and the extractive sector, have continued to surface without commensurate accountability outcomes, reinforcing perceptions of impunity. These governance challenges have been further compounded by prolonged economic instability, which heighten incentives for rent-seeking behaviour and erode public-sector integrity.

Comparative experiences from other countries illustrate the importance of sustained implementation, inter-agency coordination, and visible results. Angola, for example, improved its CPI score by 14 points over a decade through gradual but deliberate reforms, including strengthened enforcement, recovery of stolen and illicitly acquired assets, enhanced prosecutorial action, and strategic communication of anti-corruption gains.

These efforts attracted attention from stakeholders and reinforced confidence among investors and governance experts, demonstrating that consistent implementation, rather than policy adoption alone, can yield tangible improvements in perceptions over time.

Over the past decade, Zimbabwe’s CPI performance has been informed by nine independent external data sources, each applying distinct methodological frameworks to assess public-sector integrity.

These sources, including international financial institutions, policy research organisations, and private risk assessment firms such as the World Bank, World Economic Forum, and African Development Bank, evaluate risks related to bribery, misuse of public funds, abuse of public office, state capture, and the effectiveness of anti-corruption mechanisms.

Understanding the methodological focus and weighting of each source is essential, as each contributes uniquely to the composite CPI score.

A detailed analysis of these sources enables policymakers, civil society actors, and reform advocates to identify the structural, institutional, and behavioural drivers of Zimbabwe’s CPI performance. Some sources prioritise regulatory quality and institutional capacity, while others focus on business experiences and governance risks, revealing areas where weak enforcement, limited inter-agency cooperation, and opaque decision-making are most visible.

This evidence-based approach provides a foundation for targeted reforms, strengthened coordination among oversight institutions, and more effective communication of anti-corruption outcomes.

Going forward, Zimbabwe’s performance will most likely depend less on the adoption of new frameworks and more on credible implementation, enforcement, and accountability.

Strengthened inter-agency cooperation, particularly between investigative, prosecutorial, and oversight bodies, alongside transparent public communication of progress on high-profile cases and asset recovery, will be critical.

Publicising concrete gains while maintaining due process can help shift perceptions over time and rebuild confidence in the integrity of public institutions.

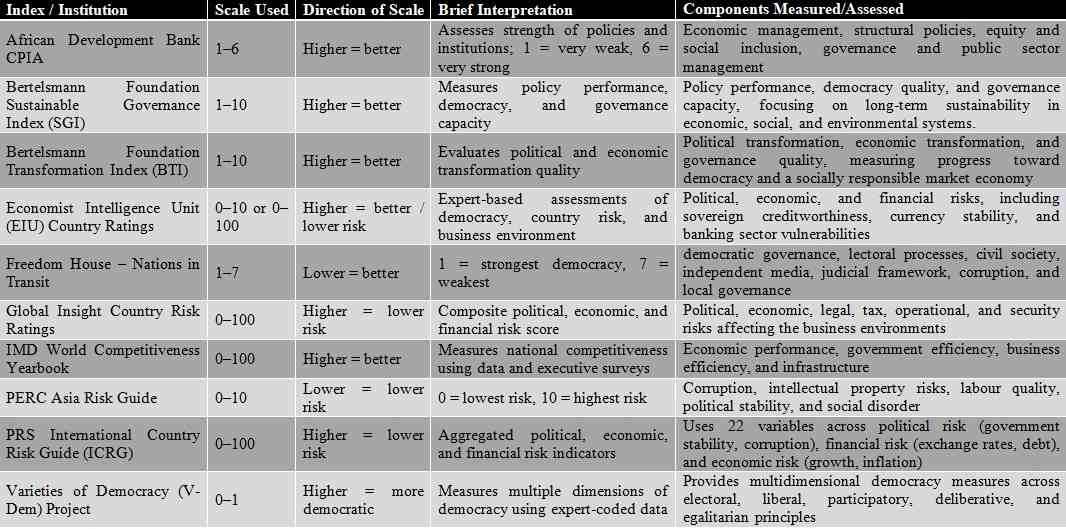

Scales and Assessments used by the external sources of data for the CPI in the context of Zimbabwe

Figure 2: Scales and Assessments used by the external sources of data for the CPI in Zimbabwe

**Source: Authors’ own analysis

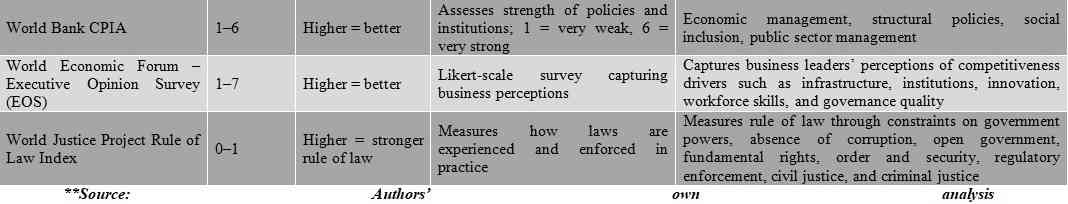

- A breakdown of the sub-indicators used to calculate the CPI for Zimbabwe

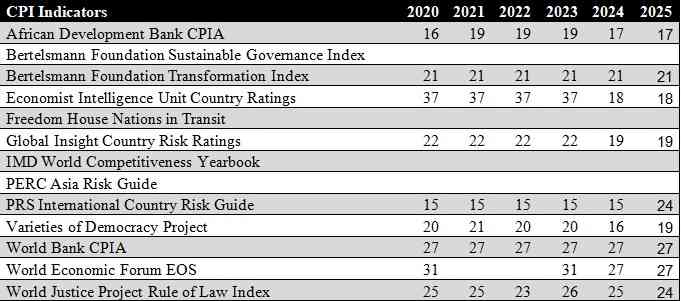

The table below shows the indicators used to score and rank Zimbabwe on the Corruption Perceptions Index typically consist of eight to nine criteria. However, the World Economic Forum's Executive Opinion Survey (EOS) is not a consistent source for providing and measuring these statistics.

For this breakdown, only the eight indicators for which Zimbabwe-specific data were available were examined.

Figure 3: Underlying Indicators Used in the Corruption Perceptions Index for Zimbabwe, 2020-2024

** Author’s own analysis

The African Development Bank's CPIA assesses the effectiveness of a country's policies and institutions in fostering sustainable growth and reducing poverty. The components measured to come up with the CPIA score capture how well a country’s policies and institutions support sustainable growth and poverty reduction (African Development Bank Group, 2026).

The African Development Bank's CPIA scores for Zimbabwe from 2020 to 2024 show a notable trend[2], starting with a score of 16 in 2020, rising sharply to 19 in 2021 due to strong policy reforms and recovery efforts post-COVID-19 such as the NDS1.

This score remained stable until 2023, reflecting a consistent institutional environment and effective consolidation of reforms. However, a slight decline to 17 in 2024 indicates emerging challenges in economic management and governance, possibly due to internal and external shocks like currency volatility (ZiG) and the Severe El Niño-induced Drought.

CPIA scores are influenced primarily by clear structural improvements or deteriorations rather than short-term events (AfDB, 2025). This consistency in scoring may explain why the World Bank's CPIA for Zimbabwe has remained static at 27 over the years. Such stability suggests that, despite potential fluctuations in governance or policy, the underlying institutional frameworks have not demonstrated significant transformation, resulting in no change in the score.

This highlights the importance of sustained, long-term reform efforts to achieve meaningful advancements in governance and public institutions, as short-term measures are insufficient to alter perceptions or enhance scores on the CPIA.

The Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) score for Zimbabwe from 2020 to 2024 remained constant at 21, indicating little change in the country’s governance and development conditions.

This stability may reflect persistent challenges such as ongoing economic difficulties including inflation and currency instability, and slow progress in social development. At the same time, any small improvements in governance, anti-corruption efforts, or institutional reforms were likely insufficient to shift the overall score, resulting in a steady rating over the five-year period.

Zimbabwe’s Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Country Ratings remained steady at 37 from 2020 to 2023, indicating a consistent performance in the assessed areas of political stability, economic performance, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality.

However, the sharp decline to 18 in 2024 likely reflects significant deteriorations in one or more of these aspects, possibly due to political instability, economic shocks such as hyperinflation or currency volatility, weakened governance, or policy uncertainty.

This trend illustrates a period of relative stability followed by a major setback in the country’s institutional or economic conditions.

The Global Insight Country Risk Ratings score remained stable at 22 from 2020 to 2023, before declining to 19 in 2024. The steady scores over the first four years suggest a consistent level of country risk, indicating relative stability in areas such as political environment, economic conditions, and external vulnerabilities.

The drop in 2024 may reflect an increase in risk factors, possibly due to economic instability, political uncertainty, policy inconsistency, external shocks, and heavy taxation on businesses.

The trend points to a period of maintained risk levels followed by a moderate deterioration in the country’s risk profile.

Zimbabwe’s PRS International Country Risk Guide score remained constant at 15 from 2020 to 2024, indicating a stable risk perception over this period before rising to 24 in 2025, indicating a significant improvement in country risk perceptions.

This flat trend may reflect several factors: the political environment remained largely unchanged, economic risks were offset by balancing factors, social and internal conflict risks did not escalate significantly, minor changes may have been masked by rounding or methodological limitations, and international perceptions of the country’s risk level remained steady.

The stability in the score suggests that Zimbabwe’s combined political, economic, and social risk profile was viewed as consistent by the PRS between 2020 and 2024, followed by a marked improvement in 2025.

V-Dem provides a multidimensional dataset capturing democracy beyond just elections, measured through five principles: electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian (Varieties of Democracy Project, 2025). For the Corruption Perceptions Index, the most relevant components are liberal democracy (rule of law, judicial independence), participatory democracy (civil society engagement, citizen oversight), and electoral democracy (free and fair elections).

These indicators reflect government accountability, transparency, and institutional integrity. From 2020 to 2025, Zimbabwe’s Varieties of Democracy score showed a slight rise from 20 to 21 in 2021, remained stable at 20 through 2022 and 2023, and then declined sharply to 16 in 2024, and then partially recovered to 19 in 2025.

This trend may reflect a minor improvement in political processes in 2021, persistent stability in democratic institutions over the next two years, and a significant deterioration in 2024 due to restrictions on political freedoms, reduced government accountability, or increased civil unrest such as those from the 2023 elections. The pattern indicates a decline in democratic quality by the end of the period.

The World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index is a comprehensive tool that measures how the rule of law is experienced and enforced in practice, not just whether laws exist on paper (World Justice Project, 2025).

It evaluates not just the existence of laws, but how effectively they are implemented and respected. From 2020 to 2024, Zimbabwe’s World Justice Project Rule of Law Index fluctuated slightly, starting at 25 in 2020, remaining at 25 in 2021, dipping to 23 in 2022, rising to 26 in 2023, and settling at 25 in 2024.

These changes may reflect real-life developments: the 2022 dip could be linked to political tensions and reports of selective law enforcement, while the 2023 rise may correspond to judicial reforms or anti-corruption initiatives. Overall, the minor fluctuations suggest that Zimbabwe’s rule of law has remained generally weak but relatively consistent, influenced by ongoing governance challenges, legal reforms, and sporadic improvements in accountability.

- Recommendations on strengthening the anti-corruption efforts in Zimbabwe

Drawing on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) as an analytical framework for assessing institutional performance and underlying governance norms, the Government of Zimbabwe can pursue a set of targeted measures aimed at strengthening public-sector integrity and reshaping institutional and organisational cultures.

While the CPI does not measure corruption as a direct incidence, it provides valuable insight into how governance systems, enforcement practices, and accountability mechanisms are perceived by experts and business actors.

Leveraging these insights allows policymakers to identify structural weaknesses, prioritise reforms that enhance credibility and effectiveness, and align institutional practices with internationally recognised integrity standards. Within this context, the following measures are proposed to address key drivers of perceived corruption and support sustained improvements in governance outcomes:

- Enhance Accountability and Transparency in Public Financial Management and Procurement:

- The government should reinforce accountability and transparency in public financial management and procurement by ensuring that anti-corruption institutions, supreme audit bodies, and oversight agencies operate with full independence, adequate funding, and legal protection from political interference. This includes prioritising timely and transparent investigations of high-profile corruption cases and applying consistent, proportionate sanctions to demonstrate zero tolerance for corruption.

- The government of Zimbabwe should expand and fully operationalise digital public procurement systems, mandating the publication of procurement plans, contract awards, beneficial ownership information, and audit outcomes in accessible, machine-readable formats.

- Strengthen enforcement of transparency, accountability and integrity principles that fully enable the reduction discretionary decision-making. This will improve governance performance and signal institutional credibility to experts, investors, and development partners.

- Strengthened horizontal and vertical accountability systems

- The government should reinforce the independence and effectiveness of institutions responsible for horizontal accountability namely the judiciary, parliament, audit institutions, and anti-corruption bodies. This includes guaranteeing secure tenure and transparent appointment processes for judges and senior oversight officials, protecting institutions from executive interference, and ensuring adequate, predictable funding. Parliamentary oversight committees should be empowered to summon officials, review public expenditure, and enforce compliance with audit findings.

- The government of Zimbabwe should foster active civil society engagement and citizen oversight, including creating platforms for public consultation, protecting the rights of civil society organizations, and encouraging community participation in monitoring public service delivery.

- Promote judicial independence

- Zimbabwe should prioritise enhancing both judicial independence and the consistency of law enforcement to foster a robust rule of law. This involves reinforcing the operational and financial autonomy of the judiciary through transparent, merit-based appointments, secure tenure, and adequate remuneration.

- Additionally, reducing case backlogs via judicial digitisation, specialised courts, and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms will enhance efficiency and access to justice.

- Law enforcement agencies must adopt clear operational guidelines and strengthen internal accountability, subjecting officers to independent oversight to ensure the equal application of laws, irrespective of political or social status. These combined efforts are essential for restoring public confidence and improving the country's standing on the WJP Rule of Law Index.

References:

African Development Bank Group (2025) Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) methodology. Available at: https://cpia.afdb.org/documents/public/cpia-methodology-en.pdf (Accessed: 02 February 2026).

African Development Bank Group, 2026. Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) methodology. African Development Bank Group. Available at: https://cpia.afdb.org/documents/public/cpia-methodology-en.pdf [Accessed 8 January 2026].

Lambsdorff, J.G., 2016. Measuring corruption–the validity and precision of subjective indicators (CPI). In: Measuring corruption. Routledge, pp. 81-100.

Transparency International, 1995. Corruption Perceptions Index 1995. Transparency International. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/1995 [Accessed 8 January 2026].

Transparency International, 2024. Corruption Perceptions Index 2024: Methodology. Transparency International. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/methodology [Accessed 8 January 2026].

Transparency International, 2024. The Corruption Perceptions Index 2024: What the CPI does not capture. Transparency International. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/news/how-cpi-scores-are-calculated [Accessed 8 January 2026].

Transparency International, 2025. Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Berlin: Transparency International. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024 [Accessed 7 January 2026].

Valérian, F., 2024. Corruption remains a global threat to development, democracy, political stability and human rights. Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024 [Accessed 7 January 2026].

Varieties of Democracy Project, 2025. About the V-Dem Project: A multidimensional and disaggregated dataset capturing democratic principles. Available at: https://v-dem.net/about/v-dem-project/ [Accessed 8 January 2026].

World Bank, 2024. Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA): Quality of policies and institutions supporting sustainable growth and poverty reduction. World Bank. Available at: https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/384071593632981223/CPIA-FAQ19.pdf [Accessed 8 January 2026].

World Justice Project, 2025. WJP Rule of Law Index 2025: Methodology. World Justice Project. Available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/downloads/Index-Methodology-2025.pdf [Accessed 8 January 2026].

***Transparency International Zimbabwe (TI Z) is a non- profit, non- partisan, systems orientated local chapter of the international movement against corruption. Its broad mandate is to fight corruption and related vices through networks of integrity. It was established in 1996 and is recognised as one of six such chapters in Southern Africa. TI Zimbabwe’s mission is to combat corruption, hold power to account and promote transparency, accountability, and integrity in all sectors of society.

Follow TI Z on: X- @TIZim_info.

Website: https://www.tizim.org.

[1] Transparency International Zimbabwe (TI Z) is a non- profit, non- partisan, systems orientated local chapter of the international movement against corruption. Its broad mandate is to fight corruption and related vices through networks of integrity. It was established in 1996 and became accredited as a national chapter in 2001, as one of six such chapters in Southern Africa.

[2] All in all, while the trends highlight periods of improvement, they also emphasize the need for ongoing vigilance to address potential setbacks.