BY any measure, Zimbabwe’s small and medium enterprise (SME) sector has become the lifeblood of the national economy. Yet it also remains its most ungovernable frontier — dynamic, creative and resilient, but chaotic, fragmented and largely untaxed.

The government’s failure to integrate this sector into a coherent framework has created a dual economy: one highly-regulated and overburdened with compliance and another — much larger — operating in the shadows, beyond tax systems, consumer protection laws and formal quality standards.

Rebuilding structured SME trade associations may sound like a bureaucratic fix, but in fact, it may be the single most effective way to restore fairness, discipline and consumer confidence in Zimbabwe’s domestic market — while finally allowing the state to collect taxes in a sustainable and non-punitive way. In this instalment, we explore ways in which the government of Zimbabwe (GOZ) can successfully do this.

The cost of disorganisation

In the 1980s and 1990s, Zimbabwe’s economy was anchored by robust, membership-driven trade associations. The Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI), the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC), the Chamber of Mines, the Horticultural Promotion Council amongst others, all represented coherent blocs of business and agriculture that the government could engage with constructively. They were imperfect, but they offered structure.

Today, that coherence has collapsed. What remains is a scattering of associations — a handful of weak SME Associations, a fading and irrelevant Indigenous Business Development Centre and Affirmative Action Group, a few of sectoral groupings — while hundreds of thousands of informal traders and micro-entrepreneurs work in isolation.

This fragmentation has created a lawless marketplace where prices fluctuate wildly, consumer complaints go unaddressed and trust between buyers and sellers erodes daily.

The absence of credible trade associations has also robbed the government of its most efficient partner in regulating and taxing commerce. No tax authority can reasonably monitor millions of informal traders one by one.

- Zimbabwe has much to learn from Rwanda’s progress

- Zimbabwe has much to learn from Rwanda’s progress

- Power crisis hits Proplastics factory

- Women urged to take advantage of Women’s Bank

Keep Reading

But organised trade associations can — through internal governance, member registries and peer regulation, which all serve as both a compliance bridge and a social contract, a sort of unwritten tripartite agreement amongst the state, the entrepreneurs and the consuming public.

Taxing without crushing it

Zimbabwe’s informal sector now accounts for an estimated 70% of the economy. It absorbs the unemployed, sustains households and keeps cash circulating in local communities. Yet this economic energy is not translating into national revenue.

The state struggles to collect meaningful taxes from informal operators, not because they are unwilling, but because there is no clear framework that makes compliance simple, fair and rewarding.

This is where structured trade associations come in. Requiring informal enterprises to organise into registered cooperatives, guilds or sector-based associations — each with its own leadership, registry and code of conduct — could turn chaos into order.

Once registered, these bodies could act as collection points for simplified presumptive taxes, similar to models used successfully in Ghana, Rwanda and Kenya.

Trade associations could also help members access banking services, credit facilities, training and markets, all tangible incentives that make formalisation worth the effort.

In return, the state gains visibility into the real size of the economy, reliable tax data and a natural conduit for policy dialogue with the sector.

Fair prices, fair play

At the heart of the current disorder is pricing anarchy. Visit any hardware stall, salon, or informal mechanic and you will encounter prices that change haphazardly depending on how you are viewed — a symptom of cost volatility, but also of the absence of any standardised pricing culture. Without associations to coordinate norms, fair competition becomes impossible.

Not long ago, I needed some construction work done on a renovation site. The first builder I met arrived in a tattered shirt, worn-out shoes and commuting by public transport — hardly the picture of prosperity.

Yet, to my astonishment, he quoted US$3 700 for the job.

A few days later, another contractor showed up — neatly dressed in overalls, driving a small pick-up truck and backed by a crew of six workers in clean overalls. His quotation? US$650 for the exact same work.

This kind of discrepancy is staggering. The first builder was basing his pricing on the needs at his household and the second builder presented a compelling case of someone running an organised small business.

Trade associations could restore sanity without enforcing rigid price controls. They could establish transparent quotation templates, sector-specific price disclosure guidelines and voluntary price catalogues that promote consistency and fairness.

This creates predictability for both for consumers, who know what to expect and for entrepreneurs, who could benchmark themselves against peers. In addition, associations could set minimum service standards and endorse members who adhere to them through recognisable certification marks.

A small artisan, builder or caterer with an association-backed quality seal immediately becomes more trustworthy to clients. That trust is not a soft value, it is the foundation of repeat business and sustainable profit, whilst the government collects its “pound of flesh”.

Collective responsibility

The old notion of “self-regulation” through trade bodies was not merely administrative, it was cultural. It promoted professionalism, mentorship and peer accountability. An organised artisan community would discipline members, who overcharged, misrepresented products or failed to deliver quality. In today’s atomised informal economy, that kind of collective responsibility has vanished.

Re-establishing structured trade associations is not nostalgic idealism. It is a practical mechanism for rebuilding an ethical business culture.

Trade associations could mediate disputes, train members and publish public directories of verified operators.

Consumers on the other hand, would gain confidence knowing they are dealing with recognised professionals and the government gains a clear line of sight into the sector.

What the government should do

The ministry of Industry and Commerce, in partnership with the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (Zimra), should spearhead the creation of a National SME Council — a coordinating platform bringing together existing business chambers, informal sector networks, consumer representatives and local government structures.

This council would not replace CZI or ZNCC and others, but complement them by giving the informal and micro-enterprise sector an institutional home.

A few key actions could set this in motion:

Simplify registration: Reduce bureaucracy for SMEs to form or join associations. Make registration free or low-cost, digital and available in all districts.

Empower associations as tax intermediaries: Allow them to collect simplified presumptive taxes on behalf of members, remitting to Zimra in bulk.

Offer incentives for compliance: Access to public procurement, low-interest loans or government-backed credit guarantees should be conditional on membership in a registered association.

Institutionalise dialogue: Create regular policy review forums where associations present feedback on taxation, pricing and consumer trends.

Support with training and governance grants: Many associations fail not from lack of will, but lack of capacity. The government and development partners could fund training in financial management, leadership and digital tools to sustain them.

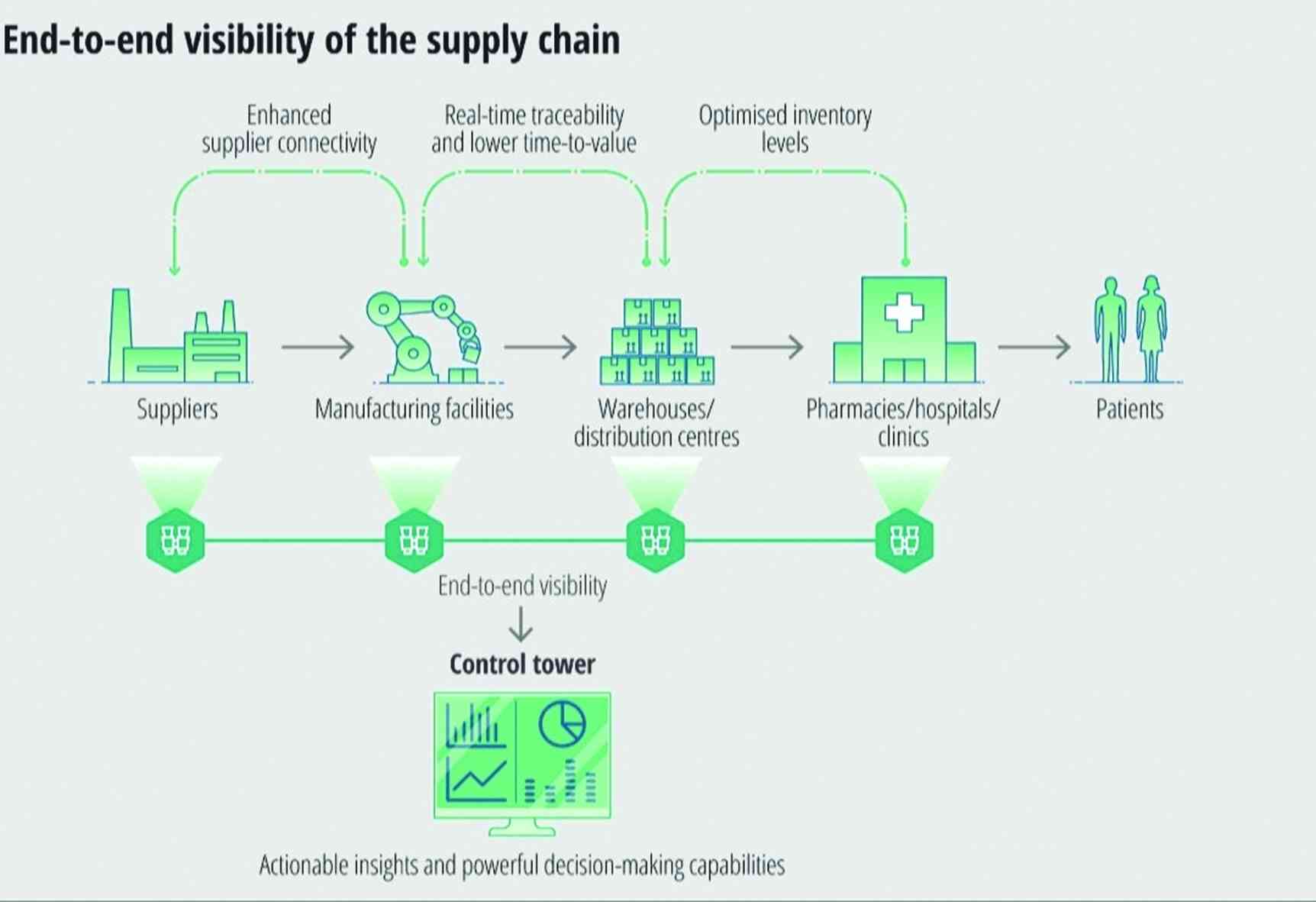

Technology as a transparency tool

The digital revolution offers the perfect lever for scaling this vision. Imagine a government-backed “SME Portal” where registered associations upload member lists, price benchmarks and certified service providers.

Consumers could search for accredited traders, rate their experiences and report misconduct.

Meanwhile, tax payments could be tracked in real time, reducing leakages and corruption.

Digital transparency also makes it easier to enforce accountability within associations. Annual reports, audited accounts and leadership elections could be conducted online, ensuring that trade bodies do not become vehicles for elite capture or political patronage — a risk that crippled many such institutions in the past.

Beyond taxes

The ultimate goal is not merely to increase revenue, but to create a developmental market — one that is competitive, transparent and inclusive. Well-organised SME associations could serve as incubators for innovation, linking small enterprises to larger value chains in manufacturing, agriculture and exports.

With proper mentorship and structured collaboration, informal producers could formalise and scale up, improve quality and meet export standards. This aligns perfectly with Zimbabwe’s industrialisation agenda.

The CZI and ZNCC already have the infrastructure to support such partnerships. What is missing is the organised grassroots base to connect with.

Formalising associations provides an entry point for labour standards, environmental compliance and consumer protection, particularly in the artisanal mining sector — the so-called “makorokoza”. It ensures that as SMEs grow, they do so responsibly and sustainably — a vital step toward building a resilient and diversified economy.

The cultural shift

There is also a deeper civic dimension to this reform. The informal economy has long been treated as a problem to be solved rather than a community to be empowered.

But taxation, when done fairly, is a cornerstone of citizenship.

When entrepreneurs pay taxes through their associations and see tangible returns — roads repaired, markets upgraded, credit made accessible — they begin to view themselves not as economic outcasts but as legitimate stakeholders in national development.

This psychological shift matters. It transforms a culture of deviance and avoidance into one of participation. It replaces suspicion with cooperation. It makes governance something done with citizens, not to them.

Learning from others

Several African countries offer practical lessons. Rwanda’s cooperatives and Ghana’s informal sector associations act as tax collection partners, dramatically improving compliance without heavy-handed enforcement. Kenya’s Jua Kali associations not only organise artisans but have become training and certification hubs, linking small producers to national procurement systems.

Zimbabwe could learn from these models while tailoring them to local realities. What matters most is political will and a mindset change within the government itself. The informal sector should not be seen as an enemy of taxation, but as an untapped partner in building a fairer economy.

A call to reorganise

Rebuilding structured SME trade associations is not a nostalgic return to corporatism. It is a pragmatic response to a fragmented economy and a demoralised consumer base. It is a way to ensure fair play in markets, protect consumers from exploitation and open a realistic pathway for government to expand its tax base without resorting to coercion.

If the ministry of Industry and Commerce leads boldly, supported by Zimra, CZI, ZNCC and local authorities, Zimbabwe could transform its vast informal sector from a fiscal headache into a developmental engine.

The future of fair pricing, consumer confidence and national revenue depends not on more predatory regulation, but on smarter organisation.

- Ndoro-Mkombachoto is a former academic and banker. She has consulted widely in strategy, entrepreneurship and private sector development for organisations that include Seed Co Africa, Hwange Colliery, RBZ/CGC, Standard Bank of South Africa, Home Loans, IFC/World Bank, UNDP, USAid, Danida, Cida, Kellogg Foundation, among others, as a writer, property investor, developer and manager. — @HeartfeltwithGloria/ +263 772 236 341.