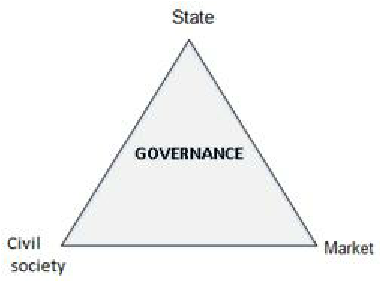

IN Zimbabwe, as in nations globally, the government frequently steps into market operations, aiming to achieve a spectrum of policy goals ranging from economic efficiency and correcting market failures to ensuring equity and distributive justice.

However, this pervasive state involvement presents a complex challenge, often leading to a subtle, yet crucial, tension with the principles of open market competition.

The intricate interaction between competition law, policy, and state activity has garnered significant international attention, both among academics and within policy circles.

This growing interest necessitates a critical re-evaluation of the roles of both competition and the state in shaping economic outcomes.

Governments organise economic activity not just through direct participation, but also through the shape and nature of regulation, explains an economic analyst familiar with the ongoing discourse. “Understanding this distinction clarifies the capabilities and limitations of competition authorities when promoting competition, especially when a broader regulatory overlay is present.”

Consequently, Zimbabwe’s Competition and Tariff Commission (CTC), like its counterparts worldwide, is tasked not only with enforcing competition laws but also with non-enforcement activities such as advocacy and advising on institutional design.

A significant aspect of this advocacy role involves addressing regulatory barriers that, while potentially serving legitimate non -competition purposes (such as licensing requirements for quality service), can inadvertently create significant hurdles for market entry and reduce overall competition. Efforts to reform such regulations are a critical part of competition policy development.

Regulatory challenges

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Keep Reading

This complex dynamic between state intervention, regulation, and market fostering is perhaps nowhere more visible than in Zimbabwe's dual economy, particularly the rapidly expanding informal sector.

Over the past two decades, this sector has grown exponentially, with estimates suggesting 76% of the population is now engaged in informal economic activities.

This trend has been driven by a combination of factors, including high inflation, poor remuneration in the formal sector, and punitive foreign exchange regulations.

However, despite these challenges, Zimbabwe’s informal sector has proven to be remarkably resilient. Through innovative marketing strategies, cross border trade, and the adoption of ICT, informal entrepreneurs have managed to build resilience and increase their earnings.

The sector has also become increasingly sophisticated, with many informal businesses now offering a range of goods and services that rival those of their formal sector counterparts.

A key factor propelling the informal sector’s growth has been the country’s deteriorating business environment. High levels of corruption, inconsistent monetary policies, and a complex tax regime have often forced many businesses to operate informally simply to survive.

Yet, the growth of Zimbabwe’s informal sector has not been without its challenges. With limited access to finance, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of social protection, many informal entrepreneurs are forced to operate in a state of constant vulnerability. The sector is also highly competitive, with numerous businesses vying for limited market share.

This complexity is acutely felt across Zimbabwe’s diverse economy, from the bustling formal retail chains like OK Zimbabwe, Spar and Pick n Pay to the ubiquitous informal tuckshops, and throughout its struggling manufacturing sector.

The stark contrast between formal supermarkets and the multitude of informal “tuckshops” or small-scale vendors exemplifies this tension.

Formal retailers operate under stringent licensing, tax compliance (including VAT), and regulatory frameworks. They often grapple with the scarcity and allocation of official foreign currency for critical imports, which can lead to higher operational costs and reliance on formal channels for sourcing goods.

This reliance can limit their competitiveness on price, especially for imported goods. Conversely, informal tuckshops, while contributing significantly to employment and convenience (often located within residential areas), frequently operate outside the formal tax net.

They often rely heavily on the parallel foreign currency market for sourcing goods, sometimes even acquiring products through unofficial cross-border trade or from informal distributors, who circumvent import duties and taxes.

While this allows them to offer competitive prices on certain goods due to lower overheads and avoidance of taxes, it creates an uneven playing field. The CTC faces the challenge of addressing these de facto regulatory barriers that either disadvantage formal players by imposing compliance costs, or allow informal ones to thrive through non-compliance rather than pure competitive merit.

Importantly, the lack of stringent enforcement on the informal sector can be seen as a form of government failure, enabling a dual market structure where competition is distorted.

Similarly, Zimbabwe’s manufacturing sector grapples with pervasive state influence and a challenging operating environment — the difficulties in accessing official foreign currency for raw material and machinery imports versus the reliance on a more expensive parallel market. For example, the Grain Marketing Board’s monopoly on staple grain procurement has often led to delayed payments to farmers, suppressing producer prices and disincentivising private sector participation in grain marketing, thereby limiting competition.

Furthermore, government policies intended to boost local production, such as import restrictions (as the phased out but impactful Statutory Instrument 64 of 2016, which restricted the import of certain goods) or agricultural support schemes like Command Agriculture, while aiming for food security or industrialisation, have often led to market distortions.

These policies can create monopolies or oligopolies, provide unfair advantages to specific local players through subsidies or preferential access to foreign currency, and stifle competition from more efficient foreign producers, often resulting in higher prices for consumers.

Global dynamics

The global economic landscape further complicates this dynamic. The impact of the worldwide financial crisis, for instance, led many countries, including some in Africa, to fundamentally re-examine the state’s role, sometimes resulting in increased government ownership in strategically important firms.

Moreover, the emergence of new economic powers, particularly China, where state intervention through state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is the norm, forces countries such as Zimbabwe to confront new forms of international competitiveness.

While some SOEs may operate akin to private firms, others have blurred lines, with profit maximisation being less central than broader state objectives.

Government intervention, as discussed, can take various forms. It might act as a “market maker”, introducing competition through competitive tendering for previously public-sector-supplied goods or opening public services to private providers. Alternatively, the state can influence markets indirectly through taxes, subsidies, or even “nudging” consumer behaviour.

While state intervention is often justified by legitimate public interest objectives, it is not immune to “government failure”. The CTC’s advocacy role becomes crucial here, not just in prosecuting anti-competitive agreements among private firms, but in advising government on how current regulations and foreign currency policies. The organisation of state entities inadvertently stifle competition or create monopolies, often leading to corruption or capture by specific interests.

For Zimbabwe, navigating this intricate landscape requires a nuanced approach. The state’s role in the economy remains both pervasive and often unclear, making precise measurement challenging.

As the nation continues to face economic pressures, the need for effective competition law and policy will only grow, demanding a careful balance between achieving state policy goals and fostering a vibrant, competitive market environment that benefits all participants, from the largest retail chain to the smallest tuckshop.

Nyawo is a development practitioner, writer and public speaker. These weekly New Perspectives articles published in the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper are coordinated by Lovemore Kadenge, an independent consultant, managing consultant of Zawale Consultants (Private) Limited, past president of the Zimbabwe Economics Society (ZES and past president of the Chartered Governance & Accountancy Institute in Zimbabwe (CGI Zim). Email – [email protected] or Mobile No. 263 772 382 852