ON June 14, 2022, lawyer and former legislator Job Sikhala was arrested and detained at Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison. He was denied bail and kept in custody for nearly two years before eventually being acquitted of all charges.

Yet, despite his acquittal, Sikhala had already been subjected to severe punishment for offences he did not commit.

Sikhala is not an isolated case. Prolonged pre-trial detention has become a disturbing feature of Zimbabwe’s justice system, with numerous victims bearing its costs.

Legal scholars view this as a shocking disregard of the Constitution, aptly captured in an academic paper titled, Courts as a Forum of Safeguarding the Right of Opposition Parties to Participate in Democratic Processes, co-authored by Zimbabwean lawyer and academic Justice Mavedzenge.

Evidence suggests that Zimbabwean courts have been reduced to appendages of the ruling elite, undermining the rule of law and separation of powers — principles indispensable to any constitutional democracy.

Victims of prolonged pre-trial incarceration justifiably feel that the courts have failed to give full effect to the Declaration of Rights, particularly the right to bail.

One such victim is Best Zuze, who spent 17 months in prison on allegations of illegally selling firearms. He lost his job, his freedom, and time with his family — only to be acquitted at the close of the State’s case.

The State’s failure to even establish a prima facie case highlighted how weak the charges were. Yet Zuze walked out of prison with no compensation, no apology — simply told: “You are acquitted, you may go home”. His life had been irreparably disrupted.

- I rejected Zanu PF scarf: Burna Boy

- NMB workers take on employer

- Mbavara eyes to resurrect Matavire’s music legacy

- I rejected Zanu PF scarf: Burna Boy

Keep Reading

Pre-trial incarceration is increasingly being used as a tool of repression, not only against perceived political opponents but also against individuals considered social “misfits”, such as armed robbery suspects.

This practice contravenes Section 70(1)(a) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe, which guarantees that all accused persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty before a competent court of law.

When an accused person is treated as guilty before trial, they suffer irreparable harm, a mischief the Constitution was designed to cure.

For Zuze, the loss of income, family time, freedom, and dignity can never be restored.

To prevent such abuses, the Constitution enshrines bail as a fundamental right, only to be denied where compelling circumstances exist.

Section 50(1)(d) states: “Any person, who is arrested, must be released unconditionally or on reasonable conditions, pending a charge or trial, unless there are compelling reasons justifying their continued detention”.

The use of the word “must” signals a non-negotiable obligation: once an accused person appears in court, release on bail should be the default. Only if the State demonstrates compelling reasons can bail be withheld.

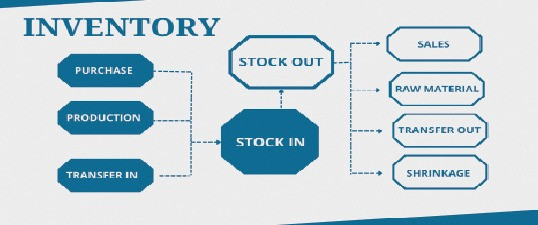

The Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act (CPEA), Section 117(2), outlines the grounds upon which bail may be denied. These include risks to public safety, likelihood of absconding, interference with witnesses or evidence, jeopardising the criminal justice system, or disturbing public peace. Importantly, the burden rests with the State to prove these circumstances.

Yet in practice, the CPEA has inverted this burden, forcing accused persons to apply for bail and prove why they should be released - contrary to the spirit of the Constitution.

Lawyer and academic Musa Kika has argued that the Act violates constitutional provisions, particularly in bail proceeding.

“There is a case to look into the Act and align it with the Constitution, to reflect the changes from the old to the new. In any bail application, the State must be applicant, while accused is the respondent,” Kika says.

The State vs Faith Zaba (Zimbabwe Independent editor) case illustrates this misalignment and demonstrates the need to amend the CPEA. Despite the State not opposing bail, Magistrate Vakai Chikwekwe insisted that Zaba submit a full bail application.

The problem is not in the court inquiring into whether compelling circumstances exist to deny bail, but in whether an accused must be making an application.

Zaba had to unnecessarily spend two nights at Chikurubi Female Remand Prison while waiting firstly for the State to establish that it had no compelling reasons to deny bail and secondly for the magistrate to deliver a full ruling on an uncontested bail application.

While the magistrate’s ruling acknowledged bail as a significant human right, his actions contradicted that principle.

Prolonged bail hearings have also raised concerns. In the cases of Mike Chimombe and Moses Mpofu, bail proceedings stretched over two weeks; both remain in pre-trial detention after 14 months.

In another matter, this writer’s own bail application took four days to be heard, was initially denied, and only granted 72 days later — on conditions the defence had originally proposed.

To show that the drafters of the Constitution were serious in avoiding punishment by pre-trial incarceration, the Constitution imposed another pre-emptory safeguard clause, which has been scarcely tested in our courts of law.

This clause seeks to ensure that even where compelling circumstances exist and bail is denied, trial must, therefore, be held within a reasonable time to the extent that the State does not abuse prison systems by keeping innocent people in pre-trial detention.

Lawyer Chris Mhike, in State Vs Blessed Mhlanga argued this Constitutional right in Section 50(6): “Any person who is detained pending trial for an alleged offence and is not tried within a reasonable time must be released from detention, either unconditionally or on reasonable conditions to ensure that after being released they (a) attend trial (b) do not interfere with the evidence to be given at the trial: and (c) do not commit any other offence before the trial begins”.

Mhike argued that 58 days of pre-trial detention was unreasonable for the charges at hand, contending that any custodial period equivalent to a prison sentence was itself punitive.

Magistrate Donald Ndirowei, however, ignored this argument as if it was never presented before him and, therefore, refused to deal with the question on what constitutes reasonable time. This remains unsettled in our courts.

Comparative jurisprudence provides guidance: Canadian courts, for instance, hold that the period from arrest to conclusion of trial for an accused not in custody should not exceed 18 months. Anything beyond that is deemed unreasonable.

At the heart of constitutionalism lies the separation of powers, designed to safeguard human rights and freedoms.

In a constitutional democracy, the judiciary must serve as the bulwark of liberty.

As constitutional lawyer, Professor Lovemore Madhuku cautions: “In the course of executing their constitutional mandate, there is bound, on occasions to be friction and tension amongst the three organs of the State. When such tensions arise, they must be addressed soberly and mutually so that the great prize, that the Constitution sought to secure for everybody, being liberty, does not become a causality”.

Regrettably, in Zimbabwe today, liberty has become that casualty.

Mhlanga is a law student at the University of Zimbabwe.