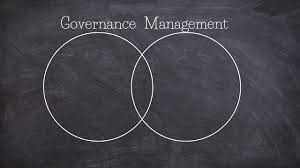

AFTER decades of observing boards across industries and continents, I have identified one dysfunction that undermines governance more than any other: the blurring of boundaries between governance and management.

This confusion not only weakens board effectiveness, but also cripples management performance, creating a cascade of organisational dysfunction that can take years to repair.

The principle is simple yet profound: boards govern, management manages. When either party crosses this boundary, both fail. Governance is fundamentally about three activities: setting strategic direction, providing robust oversight, and holding management accountable for results.

These responsibilities require boards to operate at an elevation above daily operations, maintaining perspective on long-term value creation, while ensuring appropriate controls and risk management. The board’s power lies not in operational expertise but in its independence, objectivity and ability to ask the difficult questions that management might avoid.

Yet in boardroom after boardroom, I witness directors abandoning this elevated position to wade into operational issues. They debate marketing tactics instead of marketing strategy. They critique specific hiring decisions rather than talent management frameworks. They second guess procurement choices instead of evaluating supply chain resilience. Each operational intervention represents a failure of governance discipline and a missed opportunity to add strategic value.

When boards cross into management territory, the damage is immediate and multi-faceted. Management teams, sensing the board’s operational involvement, become increasingly hesitant to make decisions.

Why take ownership of a strategic initiative when the board might override it at the next meeting? This hesitancy breeds a culture of risk aversion where managers seek board approval for decisions that should be within their authority, slowing organisational responsiveness and stifling innovation.

More insidiously, operational involvement corrupts the board’s oversight function. Directors, who have influenced specific operational decisions, cannot objectively evaluate their outcomes. They become psychologically invested in proving their operational interventions were correct, losing the independence essential to governance.

- Smuggling of gems bleeding Zim’s economy

- Erik ten Hag: Manchester United appoint Ajax boss as club’s new manager

- Zimbabwe’s smuggled gold destined for China

- New perspectives: Building capacity of agricultural players in Zim

Keep Reading

The board transforms from an oversight body into a shadow management team, but one that meets only quarterly and lacks operational accountability.

I have seen this pattern destroy value repeatedly. A technology company board that insisted on approving all vendor contracts above a minimal threshold found itself spending entire meetings on procurement details while missing fundamental shifts in their competitive landscape.

A retail board that dictated store layout decisions failed to notice deteriorating customer satisfaction metrics until market share had already eroded. In each case, operational distraction prevented strategic governance.

Understanding why boards slip into management requires acknowledging uncomfortable truths about director psychology and boardroom dynamics.

Many directors are former executives, who built their careers on operational performance. The temptation to leverage this expertise, to solve familiar problems with proven solutions, can be overwhelming.

When discussion turns to areas where directors have deep experience, the line between sharing insights and dictating decisions becomes perilously thin.

Fear also drives operational interference. When performance falters or risks materialise, boards instinctively want to take control, to fix problems directly rather than working through management. This impulse, while understandable, represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the board’s role.

Boards do not exist to manage crises but to ensure management has the capability, resources and accountability structures to manage them effectively.

Sometimes boards cross boundaries because management invites them to do so. Weak CEOs may seek board involvement in operational decisions to share responsibility for outcomes. Inexperienced management teams might genuinely need guidance on operational matters. However, even when invited, boards must resist the temptation to manage. The appropriate response is to strengthen management capability, not to assume management responsibilities.

In my board training sessions, I emphasise practical techniques for maintaining governance discipline. First, every board discussion should begin with the question: Is this a governance matter or a management matter?

If the topic concerns strategy, risk appetite, performance standards, or accountability, it belongs in the boardroom. If it concerns implementation, tactics, or operational choices, it belongs with management.

Second, boards should frame their involvement through policy rather than prescription. Instead of telling management which IT system to purchase, the board should establish IT governance policies and investment criteria.

l To read full article visit www.theindependent.co.zw.

Nguwi is an occupational psychologist, data scientist, speaker and managing consultant at Industrial Psychology Consultants (Pvt) Ltd, a management and HR consulting firm. — Linkedin: Memory Nguwi, Mobile: 0772 356 361, [email protected] or visit ipcconsultants.com.

Rather than approving individual hiring decisions, the board should ensure robust talent management processes exist. This approach maintains governance oversight while preserving management autonomy.

Third, when directors feel compelled to offer operational input, they should do so as advisors, not decision-makers. There is value in directors sharing their experience and insights, but this sharing must be clearly positioned as input for management consideration, not board direction. The distinction between advice and instruction must remain crystal clear.

Boards that maintain strict governance discipline create tremendous organisational value.

Management teams operate with clarity and confidence, knowing their authority is respected and their accountability is clear.

Strategic discussions in the boardroom are richer and more forward-looking when freed from operational distractions. Risk oversight becomes more effective when directors maintain the independence to challenge management assumptions.

The principle that boards govern while management manages is not merely a theoretical ideal, but a practical imperative for organisational success.

Every board must constantly guard against the temptation to manage; recognising that true governance performance comes not from doing management’s job, but from ensuring management can do its job effectively.

Nguwi is an occupational psychologist, data scientist, speaker and managing consultant at Industrial Psychology Consultants (Pvt) Ltd, a management and HR consulting firm. — Linkedin: Memory Nguwi, Mobile: 0772 356 361, [email protected] or visit ipcconsultants.com.