Victor Bhoroma The failure of the foreign exchange auction system and ballooning backlog provides a glimpse of how the government’s obsession with control and manipulation curtails any hopes for sustainable economic growth in Zimbabwe.

The gulf between the market exchange rate for foreign currency and the manipulated auction or interbank rate tells a story of denialism and the consequences of such to ordinary citizens and businesses.

Currently, there are varied prices for foreign exchange with the auction rate pegged at US$1:ZW$325 while the interbank rate trades at ZW$312. On the open market, the rate has accelerated to ZW$580 for electronic money and ZW$500 for cash (Zimbabwean Dollar). Mobile money and Foreign Currency Accounts (FCA) payments also attract different exchange rates on quotations.

There has been sustained overregulation of the economy with the government creating hundreds of Statutory Instruments (SIs) and playing overstretching roles in various economic sectors such as energy, agriculture, mining, banking, media and broadcasting, telecoms, health and transport services among others.

These roles are often conflicting ranging from legislation, regulation, business ownership (competitor/supplier), consuming, financing and tax collecting all at the same time or in the same sector. The economic growth witnessed in the late 20th century by Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, China and Malaysia can never be explained without the role of free market economics in those countries.

Free market policies have allowed these economies to close the gap with yesteryear economic giants such as the United States, Germany, France, Italy and Russia in a space of less than 50 years. Free market policies have demonstrated that a country can be an economic powerhouse regardless of its limitations on natural resources, area or population size.

Successful free market policy Despite the entrenched fears of market liberalism, the government successfully unbundled the inefficient Postal and Telecommunications Corporation (PTC) in the year 2000 to form NetOne (mobile telecoms), TelOne (fixed telecoms) and Zimpost (postal services). Soon after, private players (Telecel, Econet, Africom and TeleAccess) were licensed. A host of other private sector investors also got operating licenses for optic-fibre technology, internet service provision and mobile finance.

Today the telecommunications sector is a highly competitive, multi-billion-dollar industry which contributes close to 10% of Zimbabwe’s GDP and is highly integrated with financial services. The sector has churned out innovations in mobile payments, internet and data services which have improved financial inclusion in the remotest parts of the country and creating jobs and lifting thousands out of extreme poverty.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Zimbabwe’s payments ecosystem is one of the most digitalised in Africa, with over 97% of national payments being done through electronic means. Free market policies could have been instituted in the foreign exchange market, in agriculture, electricity generation, broadcasting, railway transportation, aviation and grain marketing thereby unlocking multiplier effects to the whole economy in terms of enterprise growth, direct and indirect employment creation, tax revenues and innovation.

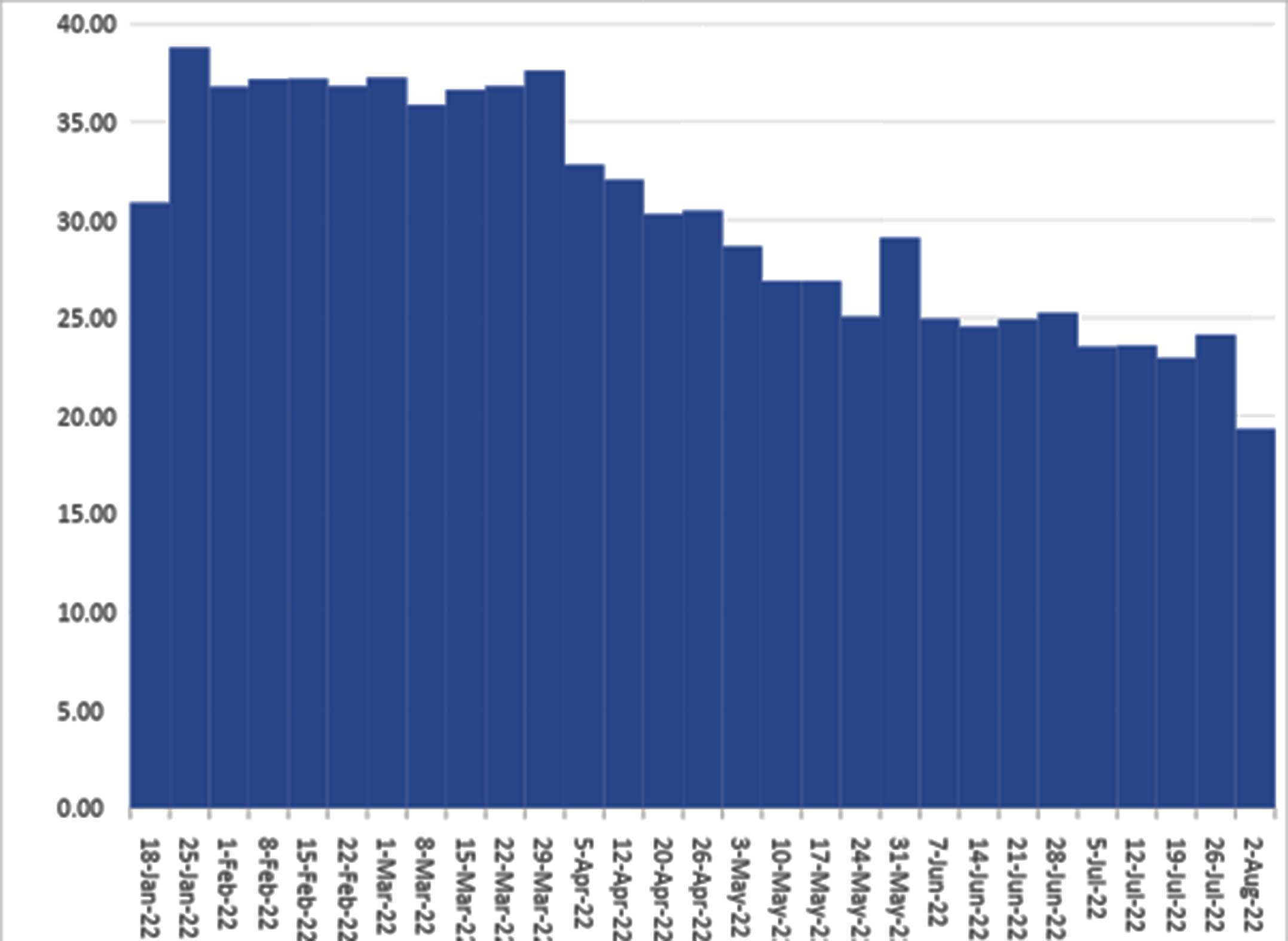

Foreign exchange market The absence of an efficient foreign exchange market has dragged on for decades with the central bank firmly fixated on controlling the exchange rate while on the other hand funding various quasi-fiscal operations that increase money supply and stoke inflation. The current foreign currency allocation system is not an auction market as it does not follow the basic principles of a Dutch auction market.

The amounts to be auctioned are never communicated beforehand, settlement is not done within two days, allotments to winning bidders are only done partially and selected bidders jump the settlement queue ahead of earlier winners. In the past three years, two economic constraints have persisted.

These are high levels of inflation and foreign currency shortage in the formal market. This is despite the fact that Zimbabwe received just under US$9,7 billion in foreign currency earnings in 2021, up 54% from the 2020 figure of US$6,3 billion. Total export receipts in 2021 jumped 38% to over US$6,1 billion from US$4,43 billion realised in 2020, while international remittances grew by over 40% to US$1,4 last year.

Despite the year-on-year growth in foreign currency earnings starting as far back as 2009, the country is stuck in man-made foreign currency shortages. Pressure on foreign currency is caused by unprecedented depreciation of the local currency and the need to preserve value. Similarly, banks and bureau de change houses are not at liberty to buy or sell foreign currency at market rates.

This means exporters and holders of foreign currency shun the formal market and feed the alternative market. To fund the auction platform and clear backlogs, the central bank relies on debt from institutions such as the Africa Import and Export Bank (Afreximbank). The central bank would not need to pile more debt on the country to support the auction system if the exchange rate was market determined as exporters and foreign currency holders would voluntarily liquidate forex on the formal market.

Capital market Foreign investor interest and net inflows to the local market have declined due to stringent foreign exchange controls, especially restrictions on repatriation of dividends and capital. Foreign investors have to wait for months for a portion of their dividends to be approved on the auction system and be queued for payments. The same applies to local investors who import raw materials and equipment.

In June 2020, the government suspended the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE) and delisted various counters from trading in order to force pension funds to invest in government securities and enforce rate stability. The country’s foreign exchange regulations have been a pain to most investors who seek formal channels to repatriate dividends. In the end, potential investors invest elsewhere on the continent where exchange rate losses are minimal, where there is unrestricted capital movement and business friendly policies.

Agriculture production Zimbabwe previously had a thriving commodity exchange (COMEZ), which was closed when the government gave the monopoly to buy and sell maize, soya and wheat to the Grain Marketing Board (GMB) in 2001. This means that there is no open access to markets for farmers since grain prices are set by the government which becomes the sole buyer of grain.

Some farmers have also fallen prey to contracting firms that set very low prices on contracting or politically connected middlemen that fleece them of their produce. Government interventions in setting producer prices in the waning local currency have also discouraged production and nurtured side marketing of agricultural commodities.

Due to overregulation, banks and private financiers shun agriculture while holders of government leased land do not develop the land. The country now relies on other African countries and other global suppliers such as Brazil and Russia for food security by importing grain and associated commodities worth US$1 billion annually.

Privatisation Privatisation has remained more of rhetoric with limited political will to see a turnaround in the affairs of state-owned enterprises. Political goals have become a priority at the expense of the dire need to resuscitate SEPs for economic growth.

Political interference and bureaucracy remain toxic in privatisation negotiations and in the operations of various state entities. Ideally, privatisation transactions would have been handled via the independent State Entities Restructuring Agency (Sera) to avoid parent ministry sabotage which is evident on commercial entities.

Political risk in most of the state entities earmarked for privatisation remains extremely high. For privatisation to succeed, there is a need for political will in removing excessive government control (thus curbing corruption). Very few investors would be interested in investing in highly indebted assets where political and legal risks are rife.

Political interference leads to short sightedness in policy formulation or implementation, bureaucracy in the awarding of licences or permits to new entrants (blocking competition), lack of transparency, artificial shortages, mismanagement and inefficient service provision of public goods and services.

Free market policies require strong institutions such as rule of law, protection of property rights, enforcement of contracts and an independent judiciary. It is true that there are no pure free market economies in the world (even in first world countries) with most countries practising different levels of mixed economics.

However, the degree of freedom in the economy relates positively to growth in private sector investment and economic prosperity. Overregulating the economy has dented Zimbabwe’s economic recovery path. There is a cause now more than ever before to let free market policies lead in order to reindustrialise the economy, attract investment, grow the tax base, create employment, and reduce levels of extreme poverty in the country.

This does not mean the government absolving core responsibilities of providing a safe and stable business environment, providing public goods, and managing the negative effects of economic growth such as pollution or environmental degradation among others.

First world countries and Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea) have repeatedly demonstrated that political objectives and provision of public goods can still be met in an economy with free market policies that promote business growth.

- Bhoroma is an economic analyst. He holds an MBA from the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). — [email protected] or Twitter @VictorBhoroma1.