THE case of State v Makedenge has ignited public debate and exposed a troubling gap in Zimbabwe’s criminal law.

Zvikomborero Maria Makedenge, a United States–based woman, is facing a charge of aggravated indecent assault following allegations that she had non-consensual sexual intercourse with a 16-year-old boy.

Many have questioned why, given the gravity of the allegations, the charge is not rape.

According to the State outline, it is alleged that Makedenge followed the complainant into a bedroom, closed the door, twisted his arm until he was overpowered, tied his hands with an electric cable, pushed him onto a bed, and then forced him to have sexual intercourse.

These allegations, if proven, describe conduct that society instinctively recognises as rape. Yet, under Zimbabwean law, the charge of rape is legally unavailable in such circumstances.

The explanation lies in the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act (Chapter 9:23). Sections 61 to 87 of the Act do not recognise the rape of a male by a female.

Rape, as currently defined, is a crime that can only be committed by a male against a female. Consequently, the State has charged Makedenge under section 66, which deals with aggravated indecent assault — an offence covering non-consensual penetration committed with indecent intention.

- ED’s influence will take generations to erase

- Fresh land invasions hit Whitecliff

- ‘Govt spineless on wetland land barons’

- Govt under attack over banks lending ban

Keep Reading

In this case, the allegation is that the accused forced the complainant to penetrate her without his consent. While this conduct involves sexual penetration and violence, the law classifies it as aggravated indecent assault rather than rape solely because of the gender of the alleged perpetrator and victim.

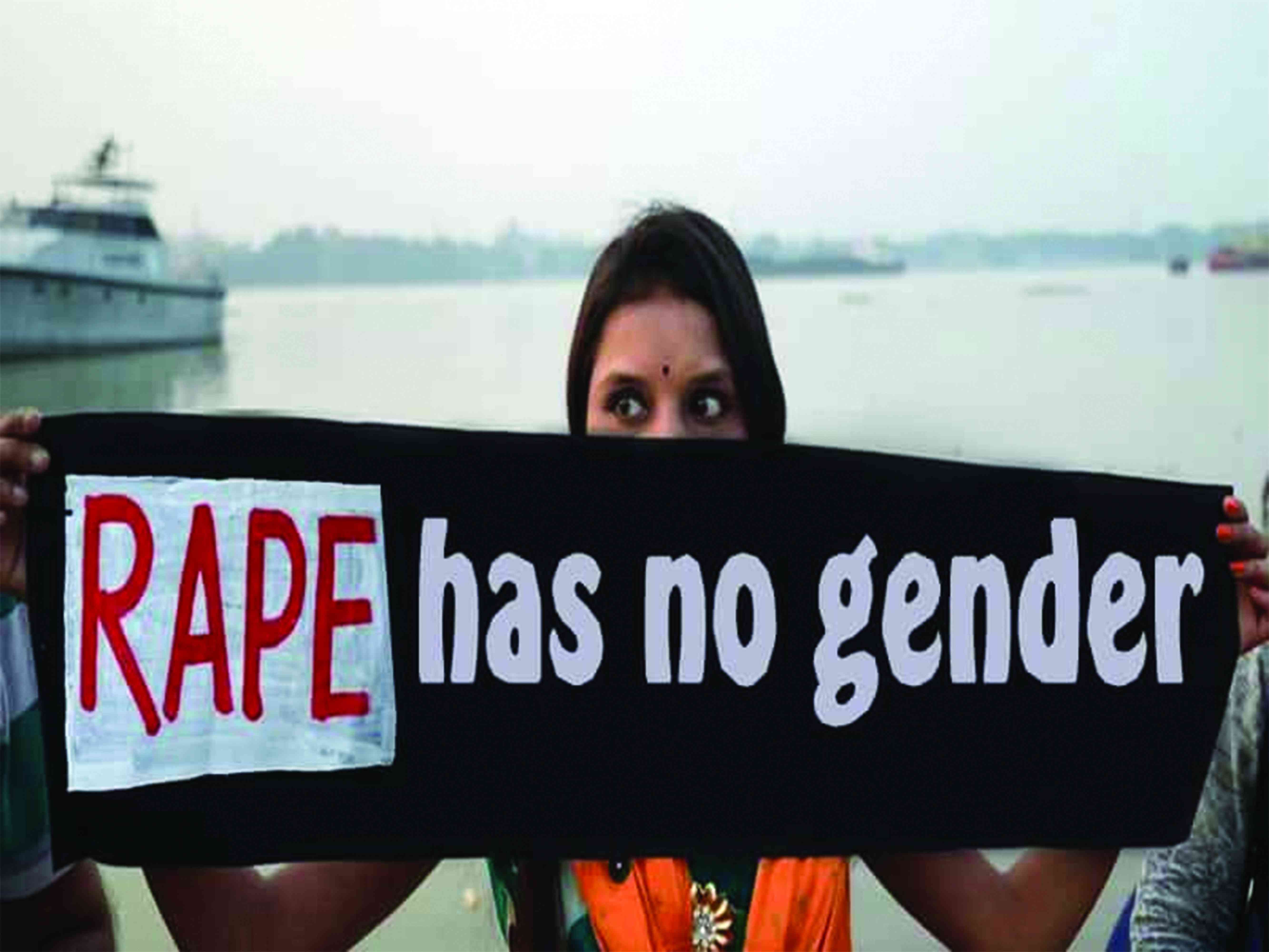

This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question: If a man who forces a woman to have sex commits rape, why does the law refuse to describe the same conduct as rape when a woman allegedly forces a man to have sex?

There is compelling merit in the argument that rape should be a gender-neutral offence. Section 56(1) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe guarantees equality before the law and equal protection and benefit of the law for all persons, regardless of gender.

Equal protection must mean that male victims of sexual violence are recognised and protected with the same seriousness as female victims.

Respected legal scholar Geoffrey Feltoe has long argued that the distinction between rape and aggravated indecent assault is artificial and outdated.

In his commentary on the Codification and Reform Act, he proposes that the two offences be merged, stating: “It would make good sense to merge these two offences together and make any non-consensual penetrative sex act rape.

These two offences are equally serious, involving sexual invasion of the complainant”.

Comparative jurisprudence strengthens this argument. South Africa’s Sexual Offences Act adopts a gender-neutral definition of rape.

Section 3 provides that any person who unlawfully and intentionally commits an act of sexual penetration without consent is guilty of rape.

“Any person who unlawfully and intentionally commits an act of sexual penetration with a complainant, without the consent of the complainant, is guilty of the offence of rape,” it states.

Under such a framework, the allegations in State v Makedenge would clearly constitute rape, irrespective of the accused’s gender.

Zimbabwe’s current framework produces troubling inconsistencies.

Aggravated indecent assault may be committed by persons of any gender against persons of any gender and includes non-consensual penetration.

Yet where sexual intercourse occurs between a male perpetrator and a female victim, the offence becomes rape. Where the same act occurs with the genders reversed, it does not.

This anomaly is not new. In State v Chikunguruse HH-206-2004, decided before the current Act, a woman who forced a six-year-old boy to penetrate her was convicted under the Sexual Offences Act, not for rape.

Even under today’s law, the outcome would be the same.

The High Court ultimately imposed a sentence of five years’ imprisonment, with two years suspended, meaning the offender served three years for conduct that would almost certainly have attracted a far harsher sentence had it been committed by a man. The disparity is stark when sentencing provisions are compared.

Aggravated indecent assault carries a maximum sentence of 15 years’ imprisonment, while rape may attract life imprisonment in aggravating circumstances.

This legislative hierarchy suggests that rape is viewed as a more serious crime, yet the distinction is based not on the harm suffered by the victim, but on the gender of the perpetrator.

Such a framework is difficult to reconcile with constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination.

It creates the impression that sexual violence against men is legally less serious, and that women who commit acts indistinguishable from rape are deserving of lesser punishment.

The courts have previously recognised that sexual offences law must evolve to confront emerging realities.

In Chikunguruse, the High Court observed that legislative reform was necessary because common law offences were no longer adequately addressing the abuse of vulnerable victims, particularly children.

“It seems to me that the legislature, in promulgating the Sexual Offences Act, and providing a penalty section which provides for a sentence of up to 10 years imprisonment, had recognised the growing problem of the abuse of young children.

This was also an acceptance that the common law offense of indecent assault was not effectively dealing with the problem,” the High Court judge stated. That reasoning is still relevant today

The Makedenge case exposes a fundamental gap in Zimbabwe’s legal framework on sexual offences, particularly in how gender shapes the definitions of rape and aggravated indecent assault.

By failing to recognise male victims of sexual violence in law, the current framework undermines the constitutional promise of equality before the law.

Legislative reform is, therefore, urgently required to ensure that all victims of sexual violence, regardless of gender, are afforded equal protection, equal recognition and equal justice, in full fidelity to the values of dignity, equality and fairness enshrined in the Constitution.

- Blessed Mhlanga is a law student at the University of Zimbabwe and is the digital editor at Alpha Media Holdings.