The government, through the amendment of the Criminal Codification Act (Code), introduced a law that criminalises the unlawful and intentional broadcast or transmission of information or messages likely to incite violence or damage to property.

This law is encapsulated in S 164 of the Code, which states: “Any person who unlawfully by means of a computer or information system makes available, transmits, broadcasts or distributes a data message to any person, group of persons or to the public with intent to incite such persons to commit acts of violence against any person or persons or to cause damage to any property shall be guilty of an offence and liable to a fine not exceeding level 10 or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding five years or to both such fine and such imprisonment.”

Arguments have been raised asserting that this law is unconstitutional and should therefore be removed from the legal framework. Critics argue that it violates Sections 61 and 62 of the Constitution.

The question at hand is: when does a law fail the test of legality, a concept referred to as the “principle of legality”? This article aims to provide insights into this issue within the context of criminal law.

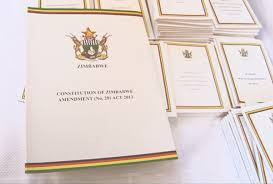

Constitution as supreme law

The Constitution serves as the supreme law of the land, providing the foundational framework for all other legislation. Section 2(1) states: “This Constitution is the supreme law of Zimbabwe and any law, practice, custom, or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.”

In simpler terms, any law that infringes upon rights protected by the Constitution cannot be deemed lawful. Consequently, laws that are ultra vires the Constitution can be challenged constitutionally and must be struck down if found inconsistent.

It is important to state at this point that Freedom of Expression is contained in the Declaration of Rights, which on the starting point is that the very purpose of a Declaration of Rights is to set rights which cannot be taken away by parliament except through an amendment of the Declaration of the Rights itself.

- ED’s influence will take generations to erase

- ‘Govt spineless on wetland land barons’

- Govt under attack over banks lending ban

- Zim Constitution must be amended

Keep Reading

This was established in American case of West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett 319 US624(1993).

Coming closer home, Section 164 of the Criminal Code therefore on the surface appears to be in line with Section 61(5) (a) of the Constitution, which aims to curb the abuse of free speech to incite violence. This was argued by the learned Magistrate Learnmore Mapiye in her judgment dismissing the Heart and Soul Broadcasting Services (HSTV) application for referral to the Constitutional Court, where the company was accused of broadcasting inciting material in which she reasoned.

“In the current case, one can say there is a constitutional matter that requires interpretation of the Constitution when Section 61(5) provides limitations to the right to freedom of expression and freedom of the media to exclude incitement to violence. The exception is the one that Section 164 is giving voice to,” she ruled.

However, this interpretation can be viewed as narrow when considering the broader implications necessary for assessing the legality of the law.

Precision in law

One fundamental issue concerning the legality of a law is its precision. Legal scholar Geoff Feltoe argues: “The criminal law must not be so widely expressed that its boundaries are a matter of conjecture.”

This view is supported by the ruling in State v. Mpofu & Another CC-5-2016, where the court stated: “The right to protection of the law entails that the law be expressed in clear and precise terms to enable individuals to conform their conduct to its dictates. A law may not be so widely expressed that its boundaries are a matter of conjecture or may be so vague that the people affected by it must guess its meaning.”

It can therefore be argued that Section 164 of the Code is excessively broad and embarrassingly vague, failing to adhere to the principle of legality. Instead of reinforcing Section 61(5)(a) of the Constitution, as ruled by the learned magistrate Mapiye, it encourages self-censorship and undermines freedom of expression.

The ambiguity lies in determining which messages may be construed as inciting violence.

For instance, playing Suluman Chimbetu’s song Sean Timba could easily be interpreted as broadcasting a message that incites violence. The lyrics, “Kana munhu anetsa batai munhu, sotai munhu, kumurova ndari,” loosely translate to “If a person causes trouble, beat them up.”

Despite its popularity, no one has been arrested for this song, including its composers. This demonstrates that enforcement of the law is subject to individual interpretations, rendering it vague and potentially dangerous in a democratic society.

Implications of vague laws

A law that is excessively broad and vague cannot meet the principle of legality and must be struck down as unconstitutional. Its trite that laws must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable citizens to regulate their conduct and avoid legal violations, this is because vague laws can lead to arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, as seen in various instances within the Zimbabwean justice system, particularly during the tenure of former President Robert Mugabe, who utilised sections of Law and Order Maintenance Act to silence critics.

Lawyer Chris Mhike articulates this concern in a Constitutional Court pleading against the constitutionality of Section 164 of the Criminal Code, stating:

“History has shown that laws that are vague, like Section 164 of the Code, generally encourage arbitrary police and prosecutorial conduct in the implementation of the law.”

This is illustrated by the handling of the case of DJ Olla 7 on March 24, 2025.

It is evident that Section 164 of the Criminal Code attempts to reintroduce provisions from a previously struck-down law (Section 50(2)(a) of the Law and Order Maintenance Act) that was invalidated by the Supreme Court in Chavhunduka & Another v. Minister of Home Affairs SC36/00.

This earlier law criminalised making false statements “likely to cause fear, alarm, and despondency”.

Importantly, it placed the burden of proof on the maker of the statements, which had to be false — not the transmitter or broadcaster — but was still deemed unconstitutional.

In that case, the court asserted: “Freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of a democratic society and is applicable not only to information and ideas that are favorably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock, or disturb the State or any sector of the population. Such are the demands of pluralism, tolerance, and broadmindedness without which there is no democracy in society.”

In conclusion, the vagueness and broadness of Section 164 of the Criminal Code pose significant threats to freedom of expression and the principle of legality. It is imperative for laws to be crafted with clarity and precision to uphold democratic values and protect citizens' rights.

- Mhlanga is a law student at the University of Zimbabwe.