Zimbabwe’s fire-fighting administration received a sobering warning from leading economists this week: the country is on the brink of industrial collapse and severe labour market distress as lending markets buckle under the weight of punishing interest rates — the highest in southern Africa.

At the core of this crisis is a systemic financial breakdown, one that threatens to extinguish hopes of economic recovery unless President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government urgently recalibrates a flawed and regressive credit system.

Their alarm was sparked by revelations from the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC) on Tuesday, exposing a grim truth — productive credit in Zimbabwe has become a luxury very few businesses can afford. In a nation already grappling with some of the region’s highest production costs, this development pushes the economy closer to the edge.

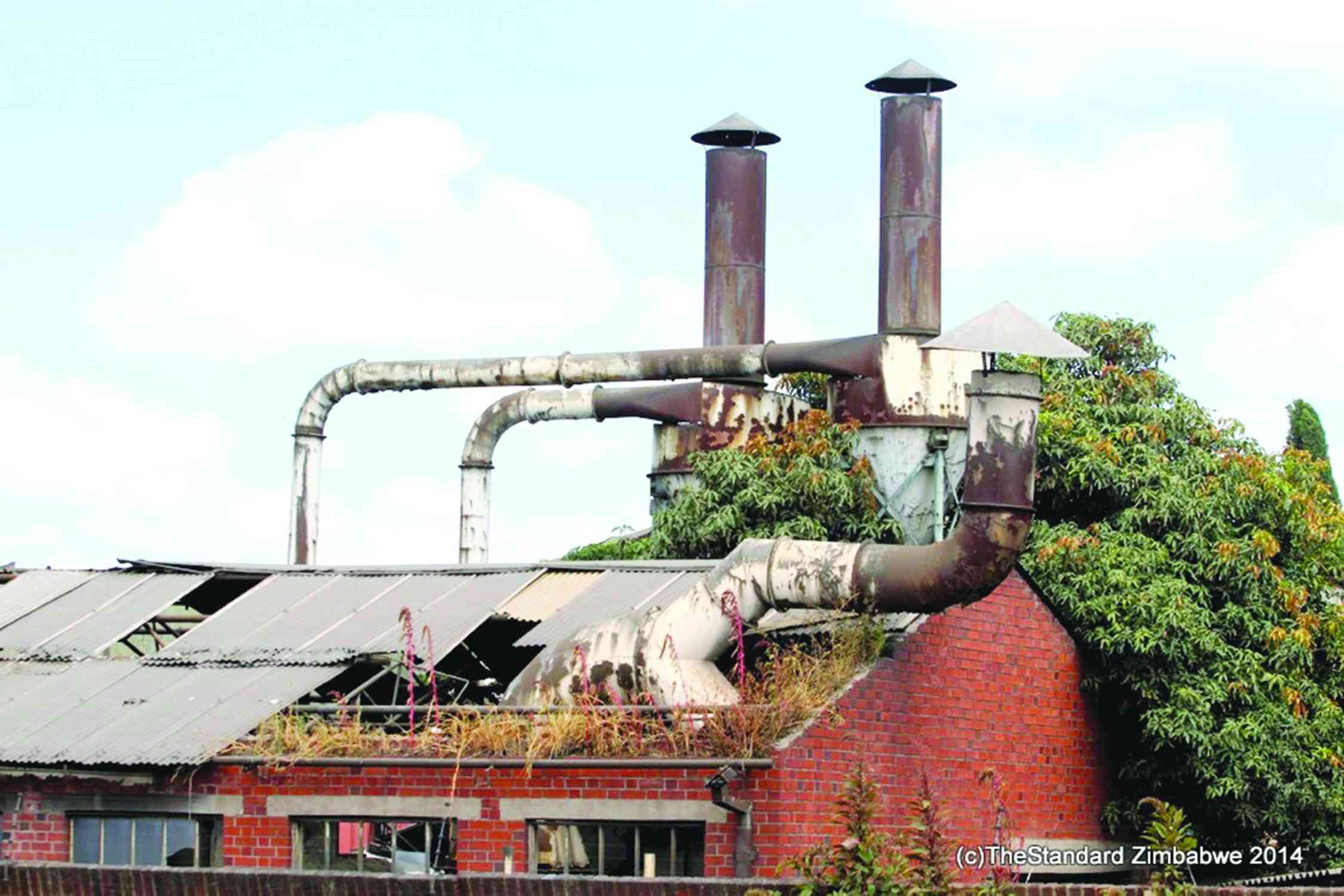

Zimbabwe is facing perhaps its most terrifying phase in a quarter-century of economic turmoil: 18-hour blackouts, 85% annual inflation — another regional record — and a currency on life support, despite claims it is backed by buffers of gold reserves.

A recent wave of disinvestment by international brands has further dimmed hopes for stability. Large corporates are seeking protection under insolvency laws, while smaller enterprises collapse under the crushing weight of taxes, policy inconsistency, and the ruthless lending environment.

And yet, despite the widespread dysfunction, the government continues to project an illusion of control. Mnangagwa’s persistent claims that Zimbabwe will achieve upper-middle-income status by 2030 are increasingly met with scepticism — both by citizens and economists.

Just last week, government contractors tasked with reviving Zimbabwe’s crumbling infrastructure revealed to the Zimbabwe Independent that they are teetering on the brink, weighed down by over a year’s worth of unpaid invoices. Following this chilling disclosure, the ZNCC demanded urgent dialogue with the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), warning that the monetary authorities risk overseeing the final implosion of an already battered economy if the current trajectory continues.

“Despite reported liquidity surpluses in the banking system, access to affordable and productive credit remains limited,” the ZNCC reported.

- Mr President, you missed the opportunity to be the veritable voice of conscience

- ED to commission new-look border post

- Zanu PF ready for congress

- EU slams Zim over delayed reforms

Keep Reading

Lending rates currently range between 40% and 47%, and the Targeted Finance Facility (TFF) has proven ineffective — reaching less than half its intended beneficiaries, according to the chamber. In a briefing paper circulated after the emergency meeting, the ZNCC disclosed banks had disbursed only about ZiG300 million from the TFF. Most applicants, particularly SMEs, have been rejected for failing to meet stringent creditworthiness criteria — raising concerns about both the design and accessibility of the facility.

Economists say Zimbabwe’s financial system is not just under pressure — it is structurally impaired. They argue that the chasm between the RBZ’s 35% policy rate and commercial lending rates nearing 50% reflects “profound systemic imbalances.” These include concentrated liquidity, currency volatility, credit risk aversion, and a pervasive lack of confidence in both the monetary framework and the local currency, Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG).

“The current spike in interest rates ranging between 40% and 47% is a clear reflection of deeper liquidity and structural imbalances in Zimbabwe’s financial system,” said Chenai Mutambasere, an economist with the Africa Centre for Economic Justice.

“While the RBZ reports a nominal surplus in liquidity, the concentration of over 80% of those funds in just a few banks means most businesses, particularly SMEs, remain locked out of affordable credit,” she said.

With the interbank market virtually defunct, liquidity remains siloed, pushing banks to impose steep lending premiums. But the model is unsustainable — it suffocates small businesses, discourages long-term investment, and makes productive borrowing unviable even for larger corporates.

“In this constrained environment, businesses are forced to borrow at high cost just to meet short-term obligations, while banks raise interest rates to maximise returns on a limited number of transactions,” Mutambasere added.

“These rates also reflect high perceived risks and ongoing currency instability, as the ZiG continues to struggle to gain meaningful traction and the economy remains heavily dollarised.”

Even with reports indicating that over ZiG16 billion sits in the banking system, the credit market remains frozen. Banks, wary of default risks, are demanding collateral most businesses cannot provide — while setting lending rates far beyond levels viable for capital formation. As a result, many companies have been pushed into informal lending markets, where terms are even more punitive.

Economist Stevenson Ndlamini, economics lecturer at the National University of Science and Technology, offered a blunt assessment: Zimbabwe’s credit market no longer functions by the traditional rules of supply and demand.

“The elevated lending rates reflect systemic risks, structural inefficiencies, and policy misalignments rather than mere profit seeking,” he told the Zimbabwe Independent.

“Addressing this requires stabilising ZiG, improving liquidity distribution, enhancing borrower creditworthiness via collateral reforms, and fostering competitive banking practices. The RBZ’s commitment to transparency and stakeholder engagement (as urged by ZNCC) could gradually narrow this gap.”

Ndlamini’s remarks echo ZNCC’s broader critique. The chamber argues that economic deterioration is being fuelled by erratic exchange rate policies, opaque liquidity deployment, and poor management of export retention thresholds.

According to the ZNCC, the RBZ’s willing-buyer-willing-seller foreign exchange market is compromised. Persistent interference in the publication of the weighted average exchange rate has undermined price discovery. The consequence is widespread confusion: businesses are unable to plan, and exporters face eroding returns on foreign earnings.

ZiG, which was introduced with much fanfare in April 2024, has failed to achieve meaningful traction. In rural Zimbabwe, the US dollar still dominates over 96% of transactions, according to the ZNCC. Even in urban centres, ZiG remains marginal. Limited convertibility, vague backing mechanisms, and a crisis of confidence continue to dog the currency.

Economist Prosper Chitambara underscored that the policy rate is no longer an effective benchmark for the cost of capital in Zimbabwe.

“The prescribed policy rate of 35% … that is just the reference interest rate,” he said.

“That is not the interest rate that individuals or businesses borrow from their banks at. So that 35% is for overnight accommodation for banks. If a bank is short and wants to borrow from the central bank, they borrow at 35%. But it doesn’t mean that for their clients that 35% will be the interest rate. The interest rate will obviously be higher.”

The government’s continued denial of economic collapse only compounds the crisis. What is now required is not aspirational rhetoric around Vision 2030 — but a hard, honest reckoning with the true cost of doing business in Zimbabwe, and bold reforms to restore confidence.

This includes revamping the Targeted Finance Facility to expand eligibility and simplify access, unlocking the interbank lending system, reducing liquidity concentration, and designing collateral alternatives to enhance SME bankability. Structural reforms must also include depoliticising currency management, embracing genuine market-based exchange rate discovery, and ensuring clear, consistent communication from the RBZ.

Absent these reforms, Zimbabwe’s formal economy will continue to shrink — leaving informal, unregulated systems to fill the vacuum. This would entrench a dual economy that is even more difficult to monitor, regulate, and rehabilitate.

As Zimbabwe grapples with this crisis, a glance across the Southern African Development Community (Sadc) region offers a stark comparison. While member states face common challenges — ranging from inflation and debt to capital flow volatility — their responses have differed markedly in design and execution.

In Botswana and Namibia, lending regimes are anchored by stable monetary frameworks and relatively prudent fiscal policies. Benchmark interest rates in these economies hover between 6% and 10%, with private sector credit relatively accessible, particularly for SMEs. In South Africa, despite macroeconomic headwinds, the policy rate sits at 8.25%, and the credit market remains a key driver of growth.

Zimbabwe, by contrast, is an outlier. Its policy rate — already the region’s highest — is further undercut by wide spreads, rampant currency risk, and pervasive macroeconomic instability. In most Sadc countries, central banks use policy rates as active tools to guide credit and inflation. In Zimbabwe, monetary instruments have long ceased to have real traction.

Sadc also promotes regional financial integration through institutions like the Development Bank of Southern Africa and the Trade and Development Bank, which offer concessionary project financing — often below 10%. Yet Zimbabwe remains largely excluded, a consequence of poor credit ratings and a long history of defaults.