It is hard enough to lose a loved one, to wake up each morning and remember that you won’t ever see them again or hear their voice.

That whatever distance there was between you, your relationship has no more opportunities to be mended. And when it comes to mothers and children, the relationship being grieved is rarely straightforward.

But few periods of mourning are as emotionally difficult as what Byron (Ashley Thomas) and Benny Bennett (Adrienne Warren) face in Disney+’s latest miniseries, when they discover that not only did they not really know their mother Eleanor (Chipo Chung), but that’s not even her real name.

In the Oprah Winfrey-produced adaptation of Charmaine Wilkerson’s epic novel, the pair learn that their mother is not Eleanor, who grew up in an orphanage, but Covey, who was raised on the idyllic coast of the Caribbean with a Chinese father and a Black mother, but fled after a number of unfortunate events and faced further tragedy away from Jamaica’s shores.

In the present, her high-achieving offspring are grieving her loss, but in a series of posthumous recordings they learn of their heritage (in a rare moment of humour, Benny delightedly exclaims: “We’re Chinese!”), and Eleanor’s darkest secrets.

They hear their mother speak about her childhood as a champion swimmer and surfer and her love for the ocean that she would eventually pass down to them. Covey’s parents only passed down pain, her mother abandoned her at age 11 and she spent the rest of her childhood in the care of her gambling-addict father who drove her family to financial ruin.

Even if Benny and Byron didn’t really know their mother, they can take some comfort in knowing that she broke the cycle and loved them as much as she did the sea. But for reasons that slowly become apparent, she couldn’t share her story.

Her evolution into Eleanor spans three continents and is filled with twists and tough decisions. Actor Mia Isaac is transfixing, subtly changing and growing as Covey is robbed of innocence and perfectly in sync with what Chung performs in the present before the character dies, making Eleanor enigmatic but soulful.

Her son Byron is now an “ocean scientist” but has long known that being Black (and now Black and Chinese!) meant he’d be considered “other” while doing his PhD and riding waves.

Outside his complex grief, we see him struggle to connect with his sister and in the workplace, where he feels consistently undervalued by white colleagues.

The prejudice the family face across the generations comes in different forms, with their Chinese grandfather never being fully accepted by the Caribbean community, Covey being sneered at as “fresh off the boat” when she reaches the UK, and Byron’s surfboard raising eyebrows in the present.

Any keen Black swimmer will find this sadly familiar (I was once told by an instructor on a lifeguarding course that my “Black skeleton” would mean I was more likely to need a lifeguard than be one), but swimming is a shared release for them all, and Covey/Eleanor credits it with helping her reach a better understanding of who she is.

As Byron says in the opening scenes, his mother taught him that: “Some people think that surfing is a relationship with the sea when it’s really a relationship between you and yourself. The sea is going to do whatever it wants.”

That is literally true and a metaphor for the show’s central premise — that Byron and Benny’s relationship to their mother is about themselves. She is an unknowable entity and learning her story is a process of coming to better understand their own identity after her death.

The series bisects into them grieving in the present, and unspooling Eleanor/Covey’s true origins in an intertwined coming-of-age story.

It seeks out difficult emotional truths which does honour the complex themes of Wilkerson’s source material, but does not always make for cohesive storytelling; at times, the two plots feel disconnected from one another.

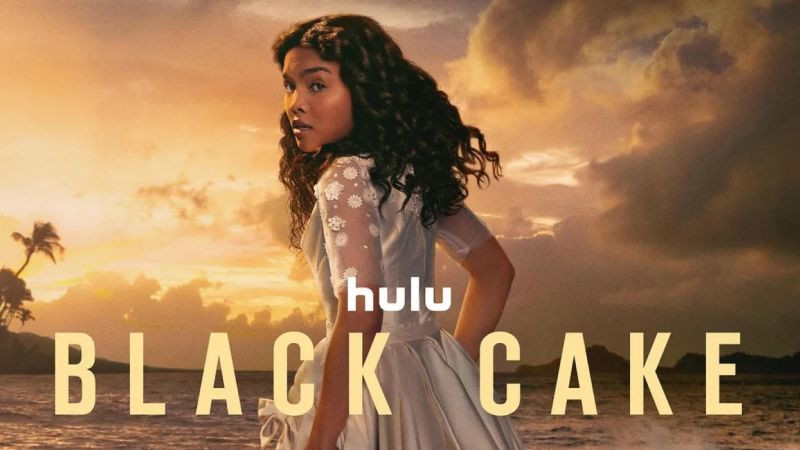

The miniseries wears its ambitions on its sleeve and ultimately achieves them with style. Though it tackles heavy themes around race, grief and gender, Black Cake is still one of the most visually stunning shows in recent memory.

Even away from the turquoise seas of 1960s Jamaica, where every character is styled to within an inch of their life in exquisite period costuming, the show has a commitment to elegance. The production design in London mansions and Pacific coast townhouses are just as striking, and even when Covey’s life becomes difficult, it remains beautiful.

The story takes its time and the eight hour-long episodes require patience and focus, but the payoff is worth it. Black Cake is a highly intelligent and skilfully crafted piece that deserves to be slowly and thoughtfully savoured. — The Gurdian