I DO what millions of us do every day, buying data. That basic digital oxygen we now need to survive the daily hustle, whether you are in an office or on the streets.

Yet every time I buy, I am reminded of the robbery we have normalised.

Whether you are on Econet, NetOne or Telecel, we are buying bundles that come with a ticking clock. When time runs out, our paid-for megabytes vanish.

If you do not use them within that time, they expire. The network takes them back. The value disappears. You pay again. Let us be clear, this is not “service”. It is a system built around a cruel and deliberate principle, use it or lose it, even though you already paid for it.

This is reverse osmosis in our economy, money is pushed from low concentration (the poor) to high concentration (big corporates), one unused megabyte at a time.

Yet, while we are conditioned to accept this as normal, South Africa has offered a powerful lesson in what organised citizens can achieve.

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) in South Africa have declared victory after sustained pressure against data expiry, pushing the regulator, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) and telecom companies to accept the argument that forcing expiry undermines access to information and consumer rights. The principle is simple, unused data and airtime should roll over, not vanish into corporate profit.

So let me ask, why should Zimbabweans be expected to simply endure? Mobile networks continue to operate expiry rules that feel like daylight robbery, hidden behind “terms and conditions”. We should not sugar-coat this. When a company sells you something and then takes it away before you can use it, that is not innovation, it is exploitation.

- Tarakinyu, Mhandu triumph at Victoria Falls marathon

- BCC, HCC adopt results-based ambulance services

- Water rationing looms in Bulawayo

- Building narratives: Chindiya empowers girls through sports

Keep Reading

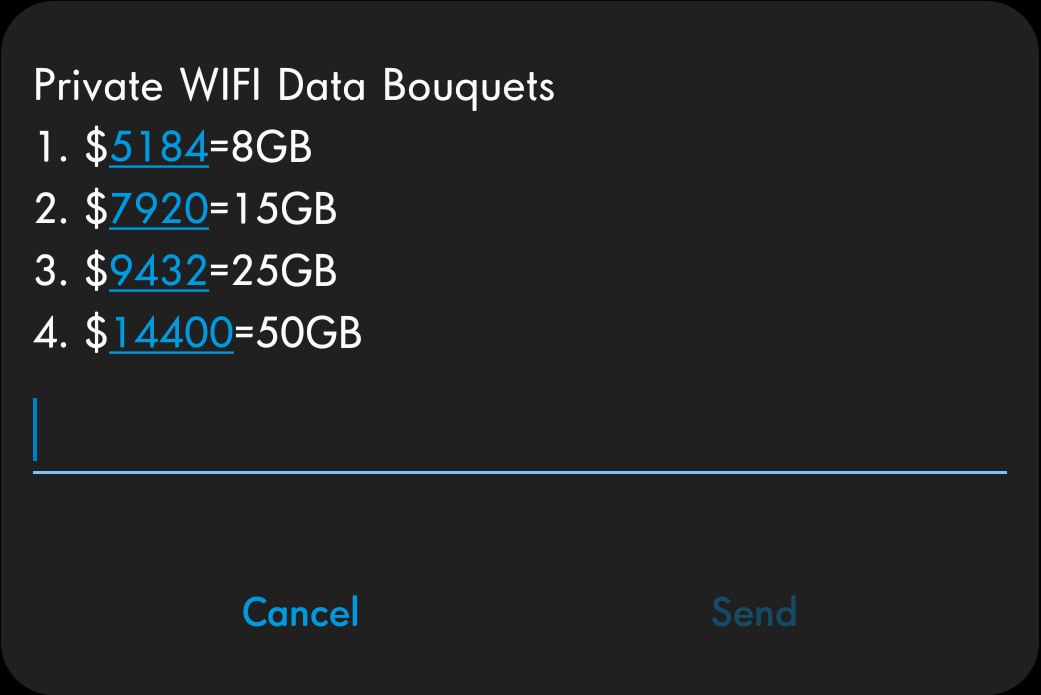

And it is worse in Zimbabwe because data is not cheap. Families are already under siege, poverty wages, school fees, fuel costs, punishing health bills, and a collapsing public service. People do not buy bundles because they have plenty. They buy them in fragments, one dollar here, two dollars there, stretching every megabyte like it is maize meal. This is why I reject the lazy argument that “people can just buy monthly bundles”.

Poverty should not be punished through expiry. The poor do not buy weekly bundles because they love weekly bundles. They buy them because that is all they can afford.

But here is what makes the system even more outrageous, data is not perishable. It does not rot like vegetables or evaporate in thin air.

Whether telecoms call it a “service” or a “product”, the truth is simple, we pay real money for measurable units (MB/GB). If those units vanish unused, then what has been taken away is not just data, it is value already paid for. Of course, telecom companies will defend this system. They will say expiry is “standard practice”, that it helps manage congestion, that it keeps prices low, and that consumers agreed to the terms.

Let us address these flimsy defences

First, on congestion. Telecoms present expiry as if it is a technical necessity, but the reality is simpler. Expiry is not network management, it is revenue management. Or put differently, congestion is an engineering problem. Expiry is a business model. Do not confuse the two.

Network capacity is managed through investment, fair-use rules, and pricing structures, not through deleting value customers have already bought.

Second, on affordability. We are told cheap bundles are only possible because people lose unused data. But if “affordable data” depends on citizens losing what they paid for, then that is not affordability, it is extraction.

Third, on the fine print. Telecoms hide behind the phrase “terms and conditions” as if it ends the discussion. Yet calling it “terms and conditions” does not cleanse it. Exploitation can also be written in fine print. Disclosure is not the same as fairness. A hungry person can “agree” to many things.

Finally, on the prepaid model. Telecoms sometimes argue that expiry is normal for prepaid products. But again, we must not be confused by jargon. Prepaid is not a licence to confiscate. Prepaid should mean you pay before you use. It should not mean you lose what you paid for.

Dear Reader, this is where Zimbabwe must have an honest conversation about digital justice. The modern economy has moved online. Government services, universities, banks, remittances, business advertising, everything is now mediated through the internet.

Which means access to data is not a luxury, it is a right, tied to dignity, education, livelihoods, and citizenship. When data expiry is enforced through corporate policy with minimal regulatory pushback, the effect is not just economic, it is political. It narrows who gets to participate in society. It creates a digital caste system, connected elites and disconnected masses.

So what should be done?

First, the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe must act like a regulator, not a spectator. It must protect consumers by ensuring that unused data and airtime do not expire, but roll over until used.

Second, Parliament’s relevant portfolio committees must treat this as a real public- interest issue. Citizens cannot only speak through frustration on social media. We need hearings, more formal complaints, and sustained public pressure.

Third, Zimbabweans must stop accepting exploitation as tradition. South Africa has shown that organised pressure matters. It can move regulators. It can force policy change. It can restore consumer rights.

Dear Reader, when a society normalises the expiry of what people have already paid for, it is not only data that disappears. Trust disappears. Dignity disappears. The very idea that citizens deserve fairness disappears.

Our data should not expire

If anything must expire, it is this culture of digital exploitation. We deserve roll-over just like what has happened in South Africa. We deserve respect. We deserve justice, even in megabytes.

Zamchiya holds a PhD in International Development from Oxford University. He is a political analyst, who writes in his personal capacity. He can be contacted on [email protected]