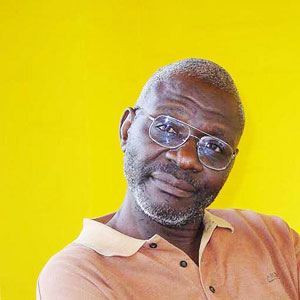

SHIMMER Chinodya (SC) is undoubtedly one of Zimbabwe’s finest writers. Besides textbooks, he has produced prose narratives, poetry as well as drama. From his early days as a curious schoolboy to his impactful work as a writer and educator, Chinodya reflects on his journey, the legacy of Zimbabwe's literary scene, and the ever-evolving role of books in shaping minds. The Zimbabwe Independent’s Eddie Zvinonzwa (EZ) speaks to the author in this interview. Below are the excerpts:

EZ: Who is Shimmer Chinodya?

SC: It’s me. Ndiri chikomana. (I am a small boy). I am 68. but I don’t feel like I am that age. I feel like I am 50. However, age has its toll and everything starts going wrong. Your eyes, your ears, your legs, your teeth but there is something else about growing up to 68. My father died when he was 70, and I am left with two years to get to that age. He was able to live through the strife that I talk about in Strife. I am surprised he was able to live through that and survive. I am the father figure in my family, ndini ndinonzi baba, it’s a responsibility I cherish. I am a writer. I started writing when I was very young, in fact I was in Grade Five.

EZ: Your educational background?

SC: I attended Mambo Primary School in Gweru for my primary education and then Goromonzi High School from Form One to Six before proceeding to the University of Zimbabwe where I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Honours in English and then a Graduate Certificate in Education. However, in between there is something that happened at Goromonzi. We were expelled after demonstrating against “Call Up” – a Rhodesia Front programme that rounded up young men to go to war to fight against freedom fighters. All Form Five and Six boys were involved. I have written about this in a book titled The March and Other Pieces – which is a collection of pieces written by a group of writers at a Literature Bureau writers’ workshop in 1981, I think. The title story is my story, “The March”. So, we marched from Goromonzi, we could not use a straight road for fear of being detected by the police. We went round through Mabvuku and demonstrated for about five minutes before being rounded up and being insulted by the policemen in charge – a typical Rhoddie. It was the most traumatic experience for me then.

EZ: After expulsion, what then happened?

SC: Some of the boys I went to school with went to Mozambique, others Botswana, some found jobs. I was lucky to get a place at St Augustine’s, KwaTsambe, Santaga, that’s where I wrote my A Levels. It was a very busy year even for my writing. I was growing up.

EZ: Who was your inspiration?

- Education 5.0: Blessing or curse for UZ students?

- UZ in fees shocker

- Deliver free education, govt told

- Police break up UZ protests

Keep Reading

SC: I think it was my father. He used to bring books home, I don’t know where he was getting them but by the time I was in Grade Two or Three thereabout, I would read them. In short, I became a writer through reading. I used to confuse the first person narrative point of view. When someone wrote “I”, I thought “I” was me, but that confusion actually empowered me. Most of the books I read were first person and I said to myself that means I can write my own stories. I felt very special and had funny dreams. I thought our house in Gweru was haunted. I try to capture that in Can We Talk in “Hoffmann Street”, it is an attempt to capture the confusion of childhood. This is the time when you try to understand adults, they will tell you kuti tichambondotenga mwana kukiriniki (we are going to buy a child from the clinic). I was a questioning child – you would hear, for instance there was Reverend Mandebvu so I would ask my mother all sorts of questions such as why that reverend had no beard when he was called by that name. Then came the Gokwe experience. Gokwe did a lot. I started by writing poetry about dew in the morning. I felt I should write a novel. We would eat chakata (mobola plum), would go fishing in the dam, tichirima nemombe (working the fields with oxen). Memory Chirere thinks Dew in the Morning is plotless and I have always quarreled with him. Irene Staunton thinks Dew in the Morning and Harvest of Thorns are my best books and I am flattered by that. I was young and was experimenting but now it’s one of my favourite books. Professor Anthony Chennells says Dew in the Morning deals with the land issue but I did not know that. Ini ndaingonyora kuti sabhuku atora munda akapa mumwe munhu. (I was simply writing of a village head who takes land from one villager and gives it to another.) I did not know I was dealing with the land question.

EZ: Is Professor Chennells still around?

SC: Yes, he is teaching at the Catholic University. He wrote the preface in the Heinemann edition of Dew in the Morning.

EZ: Catholic University, with Professor Ranga Zinyemba?

SC: I didn't know that Professor Zinyemba is at Catholic University, I want to talk to him. I started Dew in the Morning while I was in Form Three and completed it while at university. Ranga gave me his room in Carr Saunders Hostel at the University of Zimbabwe over a weekend when I was writing Dew in the Morning. It must have been Easter 1976. I spent the whole weekend playing Band on the Run by Paul McCartney and Wings. I wrote the book out nicely and neatly for the typist while in Ranga’s room in Carr Saunders. He is such a nice brother to me and I have to link up with him.

EZ: How did textbooks come about?

SC: I was sweet-talked into doing it by Barbara (Makhalisa) Nkala. She is such a wonderful person, I owe so much to Barbara. She had so much faith in me and convinced Longman that a black person could also write a textbook series in English. She was quizzed and went to board meetings to convince them that Step Ahead was worth investing in. I started by doing revision practice books, so I did specimen chapters.