IT has been four years since Troy Makaza’s last solo exhibition in the country, and in that time much has changed in the world, and in his personal life.

On the bad side, COVID-19 broke out and on the better side, Makaza got married.

The artist is now father to a toddler whose second birthday comes up towards the end of the year. Makazas’ current exhibition Kufa Izuva Rimwe at First Floor Gallery in Harare reveals his response to changing circumstances and how it affected his creative output.

Evolution of subject matter is a possible consequence when an artist goes through major life changes.

In the past this has been observed in the work of Makaza’s colleagues at First Floor Gallery, Helen Teede and Amanda Mushate.

After getting married, Teed’s work exhibited a new raw sexuality and Mushate’s entangled emotions and maternal affections rose to the surface of her canvas.

In a recent social media post promoting his latest show, Makaza hints at a similar transformation stating that in a space of three years a lot had happened.

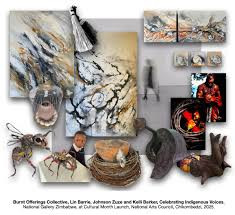

In his latest body of work, Makaza displays his usual dexterity of creating delicate landscapes through extrusions of silicone mixed with pigment.

- Zim headed for a political dead heat in 2023

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

- Tendo Electronics eyes Africa after TelOne deal

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

Keep Reading

Typically, there is both contrast and gradations in his vivid pallet. The new work shows more lateral and vertical lines that frame the work and lend a cartographic appeal.

The risqué orifices and phallic symbols that were his previous forte are gone. Tassels, ornate curtains and canopies — suggesting opulence and splendour — have replaced corky and bawdy metaphors.

In spite of the Shona proverb used for the billing of the exhibition, the artworks are tagged with obscure English titles.

At this point in his career, Makaza is not bothered with the seeming contradiction. As usual with his abstract work the initial reaction from the audience is to project familiar ideas.

The audience took pleasure in making playful associations to things they know such as the tail of a pangolin, the spine of porcupine, a Persian rug or a tiered wedding cake.

With grace, Makaza brushes such speculations aside.

“It is a chat,” he says, spelling it out over the hullabaloo of the excited gallery crowd.

He points out that various parts of the same piece are making different contributions to a conversation within the artwork.

Makaza has developed his own language out of form, colour and texture in his unique medium.

At the official opening of his exhibition, Makaza plays along to a familiar script.

His fans give him hugs, pump his hand and congratulate him.

The artist, who confesses to having suffered from depression in the recent past, could be seen posing for a group photograph and mugging for the camera.

Behind it all, the artist has become aware that those who pay attention to his work may not be interested in his pain.

That success and accolades are not the panacea for mental health issues that may be plaguing other artists.

The Shona proverb used for the title of the exhibition is a fatalistic statement that is a reminder of human mortality.

It is both a warning about unpredictable demise, and encouragement to make the most use of one’s time.

Makaza says he now values spending time with his family, away from work.

The artist, who has recently been on holiday with his family in Cape Town, South Africa, adds that it is also important for him to find time for solitude and self-reflection.

A significant development in Makazas’ work is the increased figuration, as arrestingly represented by the woman in the red dress who appears in one of the larger pieces, near a table set for three.

Her gestures are open to various interpretations, but the most important thing is the fact that she exists. The colour of the woman’s dress cannot be by chance as it is widely seen as signifying passion, confidence and sexual attraction.

Her appearance opens up new possibilities for understanding Makazas’ work, and his development as an artist.

In Kufa Izuva Rimwe, Makaza revels in domestic stability in the background of existential woes set off by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The work is a huge parenthesis that affirms life in the face of death and uncertainty.

Follow us on Twitter

@NewsDayZimbabwe