THE year 2022 could see an unprecedented scramble for grain as global supply concerns remain largely unresolved amid worrying expectations in several economies’ food and agriculture sectors.

The International Grains Council recently cut global production forecast for maize and wheat by 13 million and 11 million tonnes, respectively. The United States, the world’s leading maize producer, revised its maize output down by 9,3 million tonnes because of excessive rains, which slowed down planting.

The council also expects maize and wheat output from Ukraine — the fourth largest grain exporter — to decline by 23,5 million tonnes and 13,6 million tonnes, respectively, because of the ongoing conflict.

Global grain and agricultural inputs supply concerns have been exacerbated by logistical challenges and export bans by several grain exporters like Argentina (third largest maize exporter) and Turkey (16th largest maize exporter), and we opine that this will hit Africa hardest.

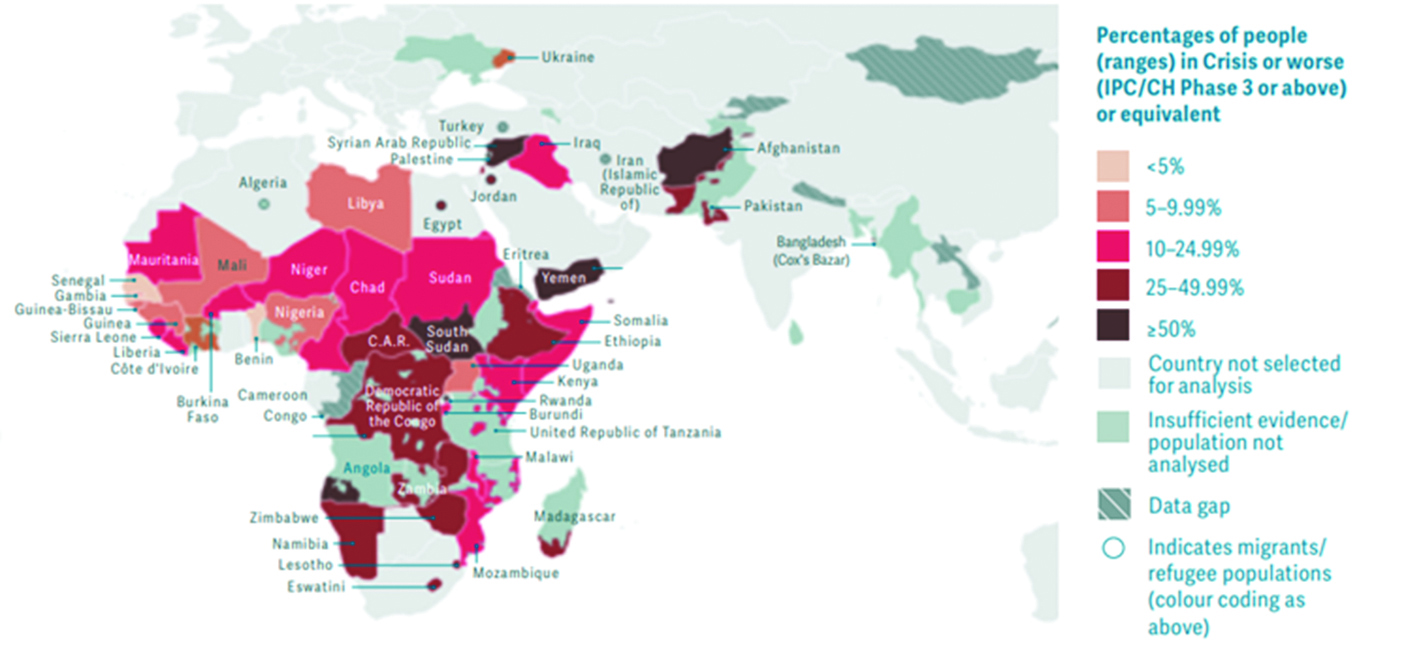

In Africa, a combination of the conflict in Ukraine and extreme weather conditions has worsened the outlook for the continent’s food security in 2022. The World Food Programme expects acute food shortages in the East Africa region on the back of an exceptionally prolonged drought and the over-arching global effects on imports of grains and fertilisers.

In Southern Africa, there are mixed output expectations in grain output. According to the US Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agriculture Service, maize output is anticipated to be below prior year’s season in Malawi, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe with a net overall decline of about 1,9 million tonnes in the region.

Authorities in Zimbabwe implicitly acknowledged the emerging food security risks by suspending import duties and removing import licences on basic commodities like rice and flour under Statutory Instrument 98 of 2022.

To add on, the government recently announced measures to direct grain deliveries to the Grain Marketing Board (GMB) after deliveries in the latest market season totalled 5 000 tonnes between April and June compared to 55 000 tonnes in the same period last year despite an above-average agriculture season.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

These measures include a permit requirement for transporting grain, granting an exemption to farmers intending to retain a portion of the produce for consumption, limiting the trading of controlled grains only to GMB and registered contractors, and offering 30% of the maize purchase price of ZW$75 000 per tonne in foreign currency.

However, the purchase price of ZW$75 000 translates to US$204,92 using the official rate and US$107,14 using the parallel market rate.

In both cases, this price falls short in comparison to the regional maize price of about US$275 on South Africa’s Futures Exchange market (Safex) and a global price of about US$345 per tonne, and this disadvantages farmers who face higher input costs this coming season while holding a depreciating currency in their bank accounts.

We opine that the immediate food security challenges that Zimbabwe faces will be largely driven by distribution inefficiencies. The GMB has traditionally circumvented this issue but at the current purchase prices, the state entity will continue to face resistance from farmers unless it adjusts in a similar manner as the government did for artisanal gold miners and tobacco farmers whose deliveries surged after the implementation of reasonable pricing and payment modalities.

We note two economic scenarios that could play out over the coming months:

Scenario 1: GMB maintains a purchase price of ZW$75 000 with 30% payable in US dollars — in this case, grain deliveries to the GMB will remain low because of the poor price and possibly better price outside GMB, stringent interstate grain transportation fines notwithstanding.

We note that forced deliveries could increase among rural farmers holding onto grain, but this would result in unwanted political effects as the nation draws closer to the 2023 elections, both locally and internationally.

The grain market will become informal and strictly USD, and this will drive demand for USD from consumers and millers from both the formal and parallel markets. The parallel market rate will continue to depreciate with inflationary effects on food prices.

Scenario 2: GMB increases its purchase price and improves USD component — appetising pricing and payment modalities will result in increased deliveries, as was the case with gold deliveries in 2021 and tobacco deliveries in 2020.

Given the stretched government coffers, funding for the purchases will likely come from issuance of treasury bills. The ZW$ payments to farmers will most likely fuel the parallel market rate given that some informal retailers have begun selling inputs strictly in USD. Inflation will likely surge from current levels as a result. However, the risk of a bad political image will be low.

Given that Zimbabwe has adequate stocks from the latest agriculture season held with subsistence farmers amid a decline in grain output in the SSA region, Scenario 2 will likely play out. In a bid to balance economic and social demands, we opine that the government could revise purchase price closer to the regional grain price levels and either improve the US dollar component or subsidise input costs. However, in both scenarios the economic outlook for the agrarian economy is discomforting.

- Mtutu is a research analyst at Morgan & Co. — [email protected] or +263 774 795 854.