FREEMAN MAKOPA GOVERNMENT has accelerated rolling out a strategy towards completely revamping the fertiliser production chain to give Zimbabwe capacity to handle destabilising shocks like the Russia/Ukraine conflict.

In an interview with businessdigest this week, Industry and Commerce minister Sekai Nzenza said she was already combing through frameworks towards addressing weaknesses in domestic fertiliser supply chains before the conflict erupted in February, holding off international freightliners at harbours amid serious production cutbacks.

It was the second crisis to rattle the world in two years, as the world battled to recover from Covid-19 pandemic-induced downturns when war broke out in Eastern Europe.

The Covid-19 outbreak had smashed production for two consecutive years, forcing the International Monetary Fund to inject US$630 billion in August 2021 to stimulate production and save haemorrhaging economies.

Russia and Ukraine hold sway in global fertiliser markets.

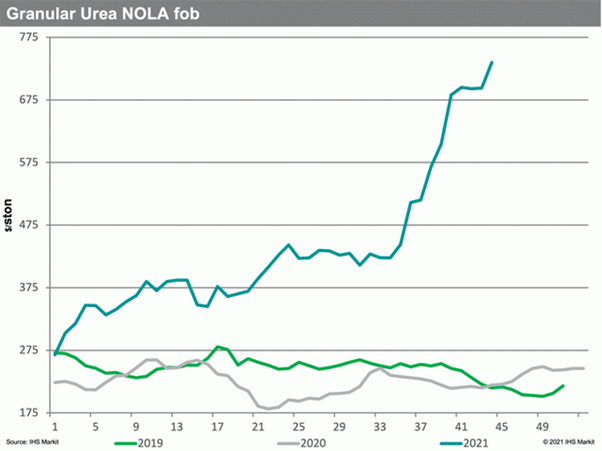

Prices have rocketed since the conflict started, and agro-led economies like Zimbabwe have been the hardest hit.

Nzenza’s plan is to swing towards full-scale domestic production utilising local resources in several enterprises mostly running under the stewardship of the Industrial Development Corporation of Zimbabwe (IDC).

War broke out at the end of Zimbabwe’s agricultural season, meaning the implications were felt less compared to economies that were at the peak of their production phases.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

But demand for fertiliser will increase as farmers return for winter cropping next month.

And in the absence of swift action, the fertiliser crisis could haunt Zimbabwe for some time, even if Russia calls off strikes in Ukraine and the conflict ends soon.

“One of my key priorities is to increase the local production of fertiliser and ensure food security,” Nzenza told businessdigest.

“The ministry has always taken a strategic approach to fertiliser production. Even before the Ukrainian crisis, as a ministry we pushed the five-year fertiliser import substitution strategy to ensure that Zimbabwe becomes self -sustainable in fertiliser production.

“This is why the government and other support companies like Zimphos and Sable are working on increasing their capacity and efficiency in fertiliser production.

“The ministry has a mandate to move up

the value chains and increase local production utilising the raw materials already available nationally,” she added.

Commenting on the fertiliser production trends this week, a local economic analyst said: “Dorowa has phosphate rock, one of the best deposits in the world.

“G&W in Rushinga has limestone, again,

some of the best in the world. We need Dorowa and Rushinga for agriculture production and food security.

“The story is that we are importing what we can make locally because fertiliser traders want to import and make money. We as a country have the raw materials to produce our own fertiliser but we do need to import sulphuric acid and ammonia gas to make fertiliser. Sable is doing that but lacks foreign currency to import ammonia gas,” the analyst added.

A strategy announced by the Industrial Development Corporation of Zimbabwe (IDC) in January said the fertiliser value chain revamp would include decommissioning a plant at Dorowa Minerals, the firm that produces phosphate for Zimbabwe’s fertiliser makers, replacing it with efficient technologies.

The IDC controls 100% shareholding in Dorowa through its fertiliser production unit, Chemplex Corporation Limited Group.

IDC chairperson Winston Makamure said Dorowa had resumed magnetite exports in the past year.

He said foreign currency generated from magnetite sales was being deployed into capital expenditure.

Makamure told businessdigest that his plan was to trim costs at Dorowa and free up resources for funding a string of projects that the IDC is undertaking, as it champions rural industrialisation efforts.

Most of the projects will be in the agricultural sector.

The IDC chairperson did not say how old the Dorowa plant was.

However, he said it last underwent major maintenance during the colonial era in 1975, which means it has been propelling Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector for 47 years since the major overhaul.

It could be one of the country’s oldest plants.

“The phosphate deposits are massive at Dorowa,” Makamure told businessdigest.

“For us to meet national demand, we definitely need to ramp up production. But the plant, which we have at Dorowa, is very old. I think the last time there was major plant maintenance was in 1975.

“We are making do with that but the next thing is we now need to move with technology. The money which we are getting from magnetite exports has started ramping up magnetite production,” he said.

Makamure said magnetite exports would be generating up to US$1,5 million per month, giving Dorowa fresh impetus to fund capital expenditure programmes currently underway.

“I think by July we should be producing 6 000 tonnes of magnetite per month,” he said.

“Now, 6 000 tonnes per month gives us US$1,5 million. That is what we will now start generating. For us to be fully self-sufficient in terms of Compound D fertilisers, we need to move away from old antiquated equipment. We need to bring new technology.

“We need to put in a completely new plant. The new plant and everything will require US$70 million. We have already started talks. I think the process has actually moved quite a stage,” Makamure added.