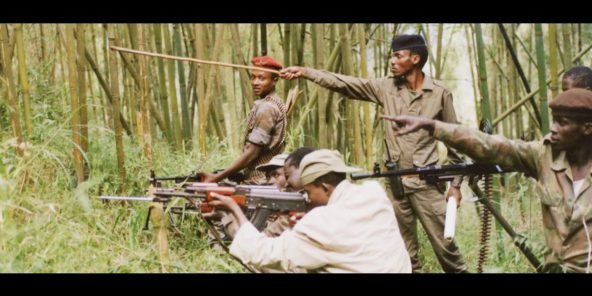

TENDAI MAKARIPE “ONE hundred thousand young men must be recruited rapidly. They should all stand so that we kill the Inkotanyi (Tutsis) and exterminate them, all the easier that… the reason we will exterminate them is that they belong to one ethnic group. Look at the person’s height and physical appearance. Just look at his small nose and then break it. Then we will go on to Kibungo, Rusumo, Ruhengeri, Byumba, everywhere.”

This vengeful message was broadcast live by a radio presenter from Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) in Rwanda on April 7, 1994.

The then Rwandan president, Juvenal Habyarimana and his counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi — both Hutus — had died in a plane crush after being shot down by unknown assailants.

Members from the dominant Hutu tribe accused Tutsis of killing the president while the latter argued that Hutus had killed one of their own to find excuses to exterminate them.

Immediately after Habyarimana’s death, Rwanda witnessed a 100-day bloodbath characterised by the merciless butchering of Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Hate speech and propaganda were identified as catalysts of the genocidal violence in Rwanda, cementing the view that these two ills can destabilise states and pose human security issues.

While Zimbabwe is not experiencing genocide, the country is not peaceful.

Norwegian sociologist Johan Vincent Galtung terms the absence of war as negative peace while arguing that what is needed in society is positive peace.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The peace, he argues, integrates human society, a view acknowledged by the Institute of Economics and Peace, which describes positive peace as the attitudes, structures and institutions that underpin and sustain peaceful societies.

Positive peace is a growing challenge in Zimbabwe and its absence is threatening to create a serious human security crisis.

One of the main trigger effects of this challenge is the proliferation of hate speech and vile language by politicians across the political divide.

Zimbabwe has seen an increase in this abhorrent attitude as the nation gears up for the March 26 by-election and next year’s harmonised plebiscite.

Freedom of expression is one of the most fundamental rights guaranteed by international and domestic legal instruments.

Article 19(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) provides that: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression,” a provision also enshrined in Section 61 of the Zimbabwean Constitution.

However, this right is being grossly abused as political players seek to demonise each other for political expediency despite the fact that Section 81 of the governance charter places limitations on some rights enshrined in the Constitution.

Even Article 19 (3) of the ICCPR also places limitations to the freedom of expression “…but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: (a) for respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) for the protection of national security or of public order, or public health or morals”.

Unfortunately, what has been unfolding in the build-up to tomorrow’s by-elections is not only a blatant disregard for respect of the rights or reputations of others but poses a danger to national security and public order.

Elected officials, political parties, candidates, opinion makers and members of the “civil” society are purveyors of hate speech.

The authority wielded by, and the amplifying effect of, mass media, social media, in particular, carries considerable weight. Both the ruling Zanu PF and opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change have created a politics of hate and intolerance in their speeches, slogans and songs culminating in violent clashes between their supporters.

Calls to crush the opposition, referring to its president as a tree that can be easily “uprooted”, promising to take “decisive action” when results do not go in a party’s favour, name-calling and labelling others as puppets while lionising the other as a capable of crushing others is a recipe for human security catastrophe.

Media and conflict resolution researcher Lazarus Sauti notes that hate language is a threat to peace, security and democratic values.

“As a matter of principle, politicians must refrain from hate language. They should instead use reconciliatory language to promote peace and co-existence in the country.

“As influential members of society, political actors in the country should avoid language that vilifies, humiliates, or incites hatred against other politicians or a group or a class of persons,” Sauti said.

“During campaigning periods, politicians use hate language to demonise their opponents using words like ‘prostitute’, dununu (fool), and mhandu (enemy). These words do not only propagate cultural violence but they further ignite physical violence.”

Another analyst Tanaka Mandizvidza said use of hate speech during elections is a rapidly evolving issue.

“Its scope and complexity will require a strategic approach that connects with and mutually reinforces the efforts of a range of stakeholders,” Mandizvidza said.

“Regulatory solutions can be controversial, difficult to reconcile when fundamental rights come into conflict and their effectiveness is limited, however, human security should not be sacrificed at all costs.”

In the same vein, the media was also called on to be careful about language use as it can fan hate speech and trigger human security issues.

Through language, certain actors, concepts, and events are placed in hierarchical pairs, named binary oppositions, whereby one element of the set is favoured over the other in order to create or perpetuate meaning.

The power relation that is embedded within this relationship for example, good versus evil or us versus them, serves to reinforce the preferred meaning within the discursive construct.